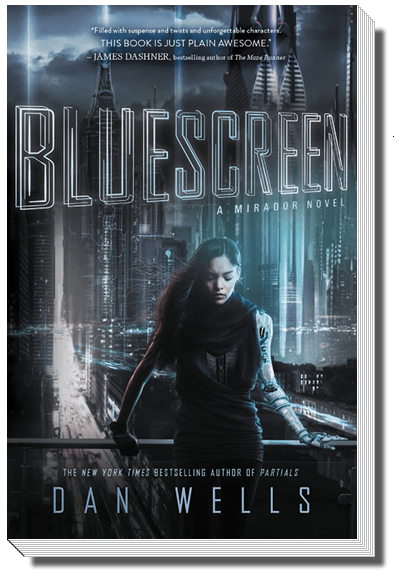

In the spirit of good science fiction, Bluescreen by Dan Wells explores not only where over-extended technology might lead but also how easily technology can slips its leash and turn dangerous or destructive. Not since reading Feed by M.T. Anderson have I experienced such a thought-provoking and chilling indictment that may encourage other readers to examine how technology—in careless or greedy hands—facilitates insidious manipulation, exploitation, and control of the individual.

In the spirit of good science fiction, Bluescreen by Dan Wells explores not only where over-extended technology might lead but also how easily technology can slips its leash and turn dangerous or destructive. Not since reading Feed by M.T. Anderson have I experienced such a thought-provoking and chilling indictment that may encourage other readers to examine how technology—in careless or greedy hands—facilitates insidious manipulation, exploitation, and control of the individual.

Set in 2050 in Mirador, a suburb of Los Angeles, Bluescreen features Anja Litz, Sahara Cowan, and Marisa Carneseca. These three seventeen-year-olds—along with Fang and Jaya—are members of the Cherry Dogs, players in an online virtual reality (VR) game called Overworld. Their lives revolve around technology, and their motto—even in the real world—is “when all else fails, play crazy” (7).

By today’s standards, life in 2050 is a bit techno-crazy, where robotic nulis perform many wait jobs and services, where cars drive themselves, and where most everyone has a dijinni. A type of wearable computing device, a dijinni is a phone, a computer, a scanner, and a credit card. It also serves as a GPS tracking system, an access code, and an identity chip. In a business district, storefronts read IDs and send adlinks to potential customers via their dijinni. Anyone with a djinni is connected to the internet and can receive chat alerts, video feeds, and navigational cues; they are also vulnerable to viruses, malware, and hackers.

In this techno-age, people also have headjacks, an advanced technology that allows wearers to receive programming like the Synestheme, a sensory program that interfaces with the dijinni to blend all five senses, enabling the user to speak in color, merge with music, or see sounds. A headjack also makes digital drugs possible. To experience a bluescreen means to feel “an overwhelming sensory rush, an unbelievable high, and then boom. Crash to desktop. Your dijinni goes down and takes your brain with it for, like ten minutes” (53).

These drugs can be obtained on a thumb drive, and like most drugs, they affect each user differently. When Anja takes Bluescreen, she sleepwalks and blacks out, endangering her life. Despite her friends’ warning, Anja’s drug use escalates and the side effects grow increasingly more sinister. A capable hacker and coder, Marisa is determined not only to solve the mystery of this software that can sever a mind’s conscious control of its body but also to discover the drug’s designer and purpose. Her detective work takes her to gang members, organized crime lords, swanky clubs for the rich with gorgeous dealers like Saif Roshan, and the darknet—“the uncharted underbelly off the internet age” (112). One of the monsters she finds there is Grendel.

When Saif realizes the extent of Marisa’s skills, he invites her to join forces with him and his contacts, but Marisa wishes instead to protect her home, to keep Mirador drug-free. But wishing doesn’t make it so, and soon, Marisa’s family is caught in the crossfire. To protect themselves from weaponized technology, she and her friends are forced to go dark, to shut off their dijinni because the only way to be safe is to hide.

As she navigates the terror of cybernetics and its puppeteers, Marisa risks her life to discover that she values trust, security, and privacy—qualities that technology has robbed from her: “We can’t trust the authorities: the government is corrupt, the cops are paid off, and the megacorps that run the world just look at us like walking bank accounts. And now with Bluescreen, we can’t even trust our friends anymore” (180). With the help of her younger brother, Sandro, Marisa also redefines happiness: “It’s not the getting; it’s the doing. Achieving things makes people happy” (107). But it’s not just achievement that brings satisfaction—it’s in getting to choose what we want to achieve.

- Posted by Donna