While Lady Julia Lindsay Mackenzie Wallace Beaufort-Stuart (aka Julie) is home from a Swiss boarding school and exploring her grandad’s Murray Estate in Strathfearn, Scotland, she wanders upon a pearl thief and receives a blow to the head. As she tries to recall the events of that fateful day on the Fearn River and to untangle a mystery of thievery, assault, and murder, she learns that memory is a strange and unreliable thing. To solve the mystery, Julie must string together the clues, like pearls torn from a necklace.

While Lady Julia Lindsay Mackenzie Wallace Beaufort-Stuart (aka Julie) is home from a Swiss boarding school and exploring her grandad’s Murray Estate in Strathfearn, Scotland, she wanders upon a pearl thief and receives a blow to the head. As she tries to recall the events of that fateful day on the Fearn River and to untangle a mystery of thievery, assault, and murder, she learns that memory is a strange and unreliable thing. To solve the mystery, Julie must string together the clues, like pearls torn from a necklace.

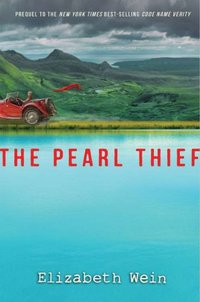

Besides being a mystery, The Pearl Thief by Elizabeth Wein fits my definition of Cultural Identity Literature, a term I coined to enlarge the traditional term multicultural literature. Cultural Identity Literature (CIL) is literature that validates diversity and the nine common determinants of cultural identity: socioeconomic class, language, exceptionality, age, religion, gender, race (which refers to biological heritage), ethnicity, and geography.

Wein’s inclusion of diverse characters aids the reader in determining that—whether a person belongs to the class of Landed Gentry, has Treacher Collins Syndrome, or endures prejudicial treatment from people who tend to hate, reject, or ignore those like Scottish Travelers whom they don’t know or even try to understand—we all possess ordinary desires and ambitions. These details make Wein’s book a catalyst for starting conversations on complex social issues, for exploring the difficulty in curing people of ingrained cultural platitudes, and for discussing the bravery of those who have so much of the world pitched against them all the time yet endure the endless strings of insults, violations, and suspicions.

With its geographic details and with traditions like ceilidh, readers also learn much about Scotland and Scottish heritage, of how the land has its own story to tell and that our ancestors and their ancient past are alive in us, making us all part ghost. Wein populates the concrete landscape of Scotland with the spirits and atmosphere of the landscape of the imagination to create Julie’s story.

Julie is determined to solve the pearl thief mystery, not only to discover what happened to her but to clear the names of the traveler folk who rescued her—to dispel the suspicions about those who deserve gratitude rather than scorn. In the process, she develops a strong friendship with Euan McEwen and his sister Ellen, a tinker girl who teaches Julie the pleasure of giving. From her, Julie learns the hardship in having one’s happiness tangled up in things we can’t keep, and Julie leads Ellen to understand that the story of a thing means so much more than what it’s worth.

As a strong female character who is pushing the boundaries of gender identity, Julie wishes for “complicated railroad journeys and people speaking . . . in foreign languages to keep [her] happy. [She] wants to see the world and write stories about everything [she] sees” (150), not feign weakness with difficult work or mental acumen. Wishing to be clever, independent, and brave, fifteen-year-old Julie is also navigating her sexuality, attempting to determine whether she prefers kissing Ellen or Frank Dunbar, a much older man serving as project foreman on the estate. From Ellen, she learns the strength, hunger, and control in how a “lad gives a kiss . . . when he means it . . . , [producing a sensation] like standing on the edge of a cliff in a gale, frightening but also marvelous” (201). The notion of paradox occurs at other junctures in the novel, with one notable example coming from Le Sphinx at the theatre, a character with a secret that Julie guesses. From Le Sphinx, Julie realizes that it takes courage and daring to be different and not be afraid of how people might react.

- Posted by Donna