Just as Rick Riordan in his Percy Jackson series employs allusions to Greek mythology, Roshani Chokshi takes her readers on a journey with twelve-year-old Aru Shah, who grew up to her mother’s story-telling with characters from Hindu mythology. Dr. Krithika Shah is an archaeologist and museum curator for the Museum of Ancient Indian Art and Culture. She and her daughter have living quarters on site, and Aru’s favorite exhibit is the Hall of the Gods, filled with a hundred statues of various Hindu deities.

Just as Rick Riordan in his Percy Jackson series employs allusions to Greek mythology, Roshani Chokshi takes her readers on a journey with twelve-year-old Aru Shah, who grew up to her mother’s story-telling with characters from Hindu mythology. Dr. Krithika Shah is an archaeologist and museum curator for the Museum of Ancient Indian Art and Culture. She and her daughter have living quarters on site, and Aru’s favorite exhibit is the Hall of the Gods, filled with a hundred statues of various Hindu deities.

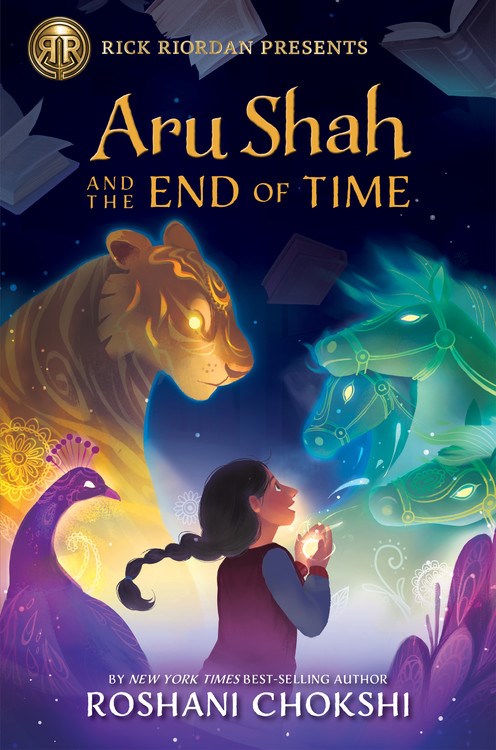

In the first of a Pandava Novel series, Aru Shah and the End of Time, readers meet Aru, who wishes to vanquish the beast that is the seventh grade. She’s on autumn break from Augustus Day School in Atlanta, Georgia, and because she’s bored and trying to impress some school mates, she applies her imagination. These invented stories abo

ut cities she has never visited and meals she has never eaten compensate for an absent father, an often travelling, busy mother, and lower socioeconomic advantages than her peers, who call her a liar—one who walks a fine line between creative and crazy.

Wearing her Spider-Man pajamas, Aru and three of her classmates enter the Hall of the Gods where Aru tells the story of the Diya of Bharata, a dusty and dull lamp that has trapped the Sleeper, a demon who awakens with the lighting of the lamp. On a dare, Aru lights the lamp, which freezes her friends and her mother and sets in motion a series of scary, world-threatening events. Her action also summons Subala, once a great figure who possesses knowledge of the Otherworld but has been transformed into a pigeon. Because his name supposedly has too many syllables, Aru decides to call him Sue, but when he objects to the gendered nature of that name, Aru calls him Boo instead.

With Boo as her mentor and guide, she walks through the Door of Many to begin her quest. As this generation’s Pandava, it is her duty–her dharma–to save the universe from Shiva, the Lord of Destruction. With Mini as her questing partner, sister, and companion, she has nine days to find the three hidden keys, to stop the Sleeper from stealing the celestial weapons, and to discover how to defeat him while lives, time, and the universe hang in the balance.

On their quest, Mini and Aru learn about greatness, about their lineage, and about the power of possibility. Aru derives many of these lessons from encountering legendary events and adversaries which she thought were confined to stories. It takes being on the brink of death for Aru to realize what she must do, but to act with one’s heart has grave consequences.

Along the way, readers learn, too, that love looks different to everyone and that greatness doesn’t simply derive from strength or valor but from the way one chooses to see the world. By looking, questioning, and doubting and by being perceptive and acting on those perceptions can also define greatness.

As I read, I appreciated this glimpse of the world from the Hindu perspective. To think about death, for example, as a parking lot—a place where you’re not stuck forever but where you waited to be reincarnated—is a reassuring metaphor. Chokshi explains reincarnation through the discoveries that Aru and Mini make. While in the Kingdom of Death, the girls encounter an area called Reincarnation Manufacturing Services. The sign at the entrance reads, “Remake, Rebuild, Relive!” Here, souls are fitted for new bodies and new lives, and Wish—a small dragonlike creature with fuzzy wings who represents the unspoken yearnings of the heart—explains the Hindu concept of samsara, for which there are no words, to these two rogue souls: “As you live, your good deeds and bad deeds are extracted from karma. Along the way, the body is subjected to the wear and tear of time. But the soul sheds bodies, just as the body sheds clothes” (285).

In another learning opportunity, Chokshi includes a glossary to shed light on some of the nuances of Indian mythology. This glossary also intrigued me, as it inspired me to see the world through the lens of another culture. Bharatnatyam, for example, is an ancient, classical dance that originated in South India. The author studied bharatnatyam for ten years, she tells readers, and defines the dance as both a creative and destructive force and as “its own kind of storytelling” (347). Many cultures use art and dance similarly.

- Posted by Donna