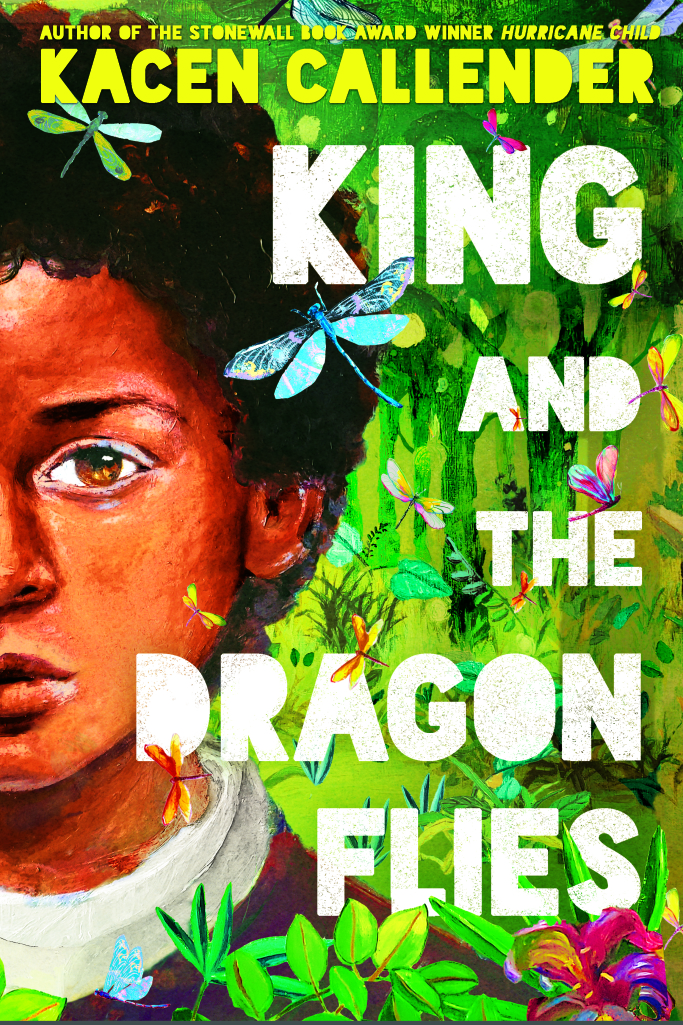

Author of the Stonewall Book Award for Hurricane Child, Kacen Callender has written a new book, King and the Dragonflies targeted for readers in grades three through seven.

Author of the Stonewall Book Award for Hurricane Child, Kacen Callender has written a new book, King and the Dragonflies targeted for readers in grades three through seven.

Set in Richardson, Louisiana, King and the Dragonflies relates the challenge that twelve-year-old Kingston Reginald James has in coping with the sudden and unexpected death of his sixteen-year-old brother Khalid. While enduring the waves of grief, King must also navigate a series of identity issues on his own since his parents are immersed in their own grief, and his older brother is no longer around to confide in.

Shy and prone to reticence, King loves anime, enjoys learning, and dreams of going to college. He is also conflicted about his name (King James? Is that a joke?), his gender identity, and the hereafter. As he reflects on his brother, dragonflies—symbols of change, transformation, adaptability, and self-realization—and the smallness of humanity in the universe, King is both inspired as well as haunted by his brother’s words: “No way you can live your life as a coward. If you’re always too busy hiding, then you’re not really living, are you?”

But that same brother, while he was alive, also told King that he could no longer be friends with Charles “Sandy” Sanders, a sensitive, quiet, and creative son of the town’s racist sheriff. “You don’t anyone to think you’re gay, too, do you?” Khalid asked.

Adding to King’s identity crisis, his dad—with “the spirit of a poet, a pastor, and maybe even a prophet” (102)—tells King: “You’ve got so much force, you can make the world bend to your will. That’s why your mom and I named you what you are, right? . . . But the world fears you. They always will. Same way they feared Malcolm and shot him. Same way they feared Jesus Christ and nailed him to the cross. . . . and some people—they’ll want to hurt you because they’re afraid. I need you to be careful” (102).

In spirit, Khalid visits King while he is asleep and tells him secrets: “secrets that are best kept hidden because sometimes people aren’t ready to hear the truth” (12). But, how can King help his friend, who is being abused, if he is sworn to secrecy? And how does a person even know what the truth is when someone wants to keep a secret?

Amidst all of that conflict and confusion, both sadness and fear fill King, who finds comfort in the lies he tells himself and those he tells others—until he finds himself caught in the web of his deception. How can he set right the wrong he has done? How will he find the courage to apologize—to Jasmine, his best friend and sometimes girlfriend; to Sandy, his kindred spirit; and to his parents who trusted him?

In addition to telling the story of a young man’s journey to self-discovery, Callender invites all readers to think critically about and to interrogate phrases like “that’s just the way it is” or about defining things based on the past instead of taking into account new circumstances, contexts, and people.

Callender not only points out how worry can prevent a person from thinking about how to be happy but also shares a key moral: “We should be who we are and like who we like, no matter who’s going to laugh” (198).

Because I have always considered the flitting dragonfly—with its massive bulbous eyes and souped-up color vision and its wings of rainbow iridescence—intriguing, I found it a fitting and symbolic reminder that we need lightness and joy in our lives and that we need to dive deeply into our feelings to understand both ourselves and our lives more fully. The dragonfly further reminds us to be in the lookout for illusions and deceits, whether external or personal, and that “the spirits of this world don’t stay dead for long” (228).

Although Callender tells a dreamy story of a boy coming to terms with who he really is in the wake of his brother’s death, perhaps the ultimate lesson from this book is that which encourages us to learn from the dragonfly, whose 30,000 facets give it a different perspective and whose compound eyes enable it to see in all directions at the same time. Perhaps, with such sight, we wouldn’t be as prone to prejudice.

- Posted by Donna