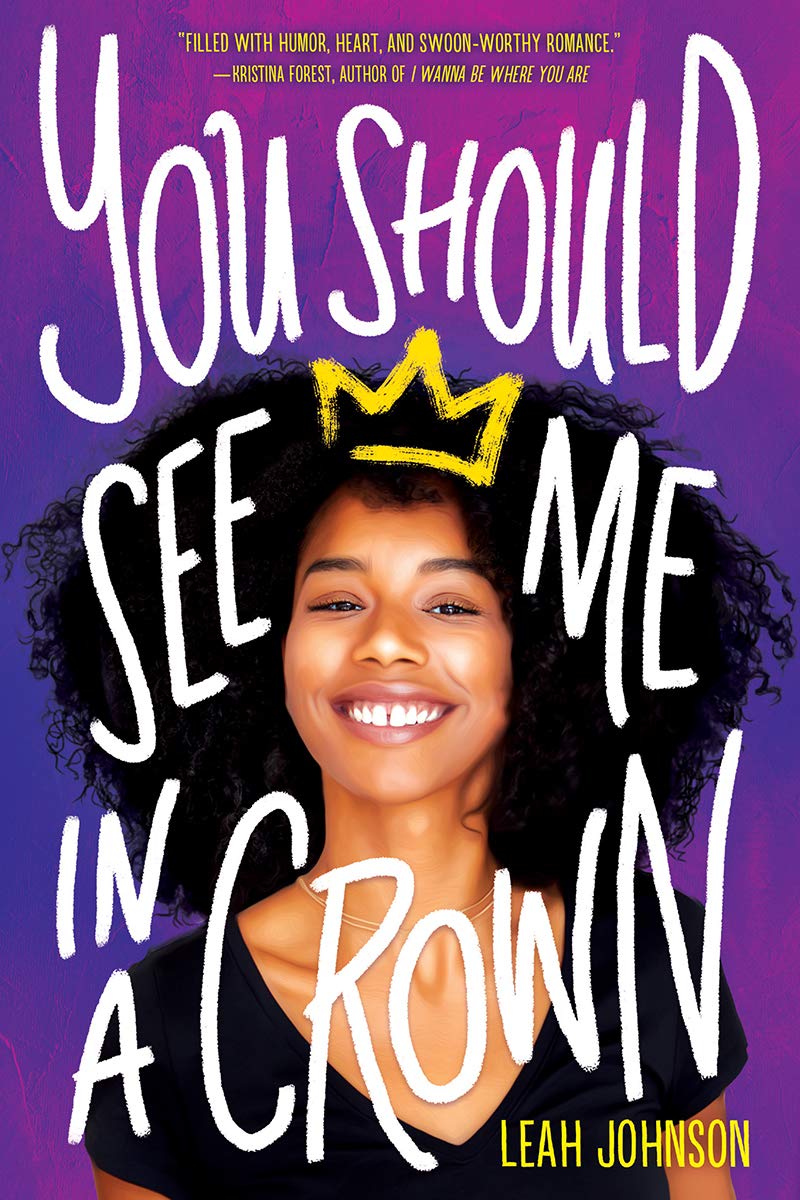

Although Leah Johnson is a writer and editor, You Should See Me in a Crown is her first novel. Set in Indiana, the story features seventeen-year-old Liz Lighty whose life has been derailed by her mother’s death to complications with sickle cell disease (SCD). Living with her grandparents where money is tight and taking care of her brother Robbie who has Acute Chest Syndrome, an inherited form of SCD, keeps Liz on edge.

Although Leah Johnson is a writer and editor, You Should See Me in a Crown is her first novel. Set in Indiana, the story features seventeen-year-old Liz Lighty whose life has been derailed by her mother’s death to complications with sickle cell disease (SCD). Living with her grandparents where money is tight and taking care of her brother Robbie who has Acute Chest Syndrome, an inherited form of SCD, keeps Liz on edge.

Because she feels like everything about her makes her stand out, Liz has mastered the art of being a wallflower. On the fringes and out of the spotlight, Liz hopes to hide that she is anxious and awkward, queer and confused, broke and brilliant. At Campbell County High School, the idea of having people’s eyes on her causes her anxiety to kick into high gear, and sometimes the overwhelming feeling of otherness comes in waves so strong they threaten to pull her under.

Still, Liz draws attention to herself with her musical talent and academic insight. Believing that musicians make the best story tellers and seeing harmony and life energy emerge in a chaos of sound, she dreams of attending Pennington College’s School of Music, an elite private college in Indiana. Bending the notes to her will, music is a thing she understands, so she applies for a scholarship.

Despite her status as class valedictorian and her impeccable audition tape, when Liz learns she has not won and cannot live out her dream without the money, she looks for alternatives. Robbie suggests she apply for the scholarship offered through the contest for prom queen. Initially, she is unwilling to subject herself to the mania of prom. In Campbell County, the whole town turns into fanatics about prom, exploding into a “heap of sequins and designer tuxes and enough hairspray to fuel the Hindenburg” (4). Liz thinks the town’s focus on prom might be impressive if it weren’t so ridiculously, obnoxiously annoying.

Driven by need and cajoled by her best friend Gabi Marino, Liz acquiesces. Petite and furious, elegant and confident, Gabi dreams of being a designer in New York. Gabi knows what she wants and dives in with full-on focus, turning Liz’s candidacy into a project. Although Liz is convinced that her friends are certified odd balls, she—one of the nerdiest nerds—allows herself to be led into the rumors and the polls and the drama.

Once she’s in the middle of the fray, Liz meets Amanda McCarthy, a girl with gorgeous green eyes who is talkative without a filter. Another queen candidate, she is also a drummer and confident in her sexuality. Mack, as she prefers to be called, has a rule to “never let terrible people get away with doing terrible things” (42), so if something is wrong, she will certainly speak up. Rachel Collins, the entitled bully, is her first target.

At one point in the contest, Gabi suggests to Liz that she keep her friendship with Mack hidden, so as not to sabotage her candidacy. Although people love drama and a little novelty, they won’t vote for a queer queen, according to Gabi. This hate comment derails Liz, who is used to being silent and shamed, but unaccustomed to having to run from prejudice delivered by her bestie. Despite the weight and impact of being different, Liz believes that she and Mack deserve good things too.

As the story unfolds, the reader encounters secrets, mysteries, and other characters intent on sabotage. With every step that Liz gets closer to making court, someone’s counter move forces her two steps back. In the process, Liz not only regains a friend she thought she lost in Jordan Jennings, a cool and collected, charming and funny young man; but runs the risk of losing Gabi.

Johnson’s book joins other books on the topic of prom, books like Prom by Laurie Halse Anderson. But it goes deeper, with ample opportunity for critical thinking on tough topics like gender expression, perception of belonging, socioeconomic status, and race.

Johnson also invites readers to think critically—not only about ally behavior and how we don’t say what perhaps we should but also about friendships. Sometimes, we look for perfection in a friend, when we humans have to be accepted on face value, complete with flaws and fears and mistakes. Because we’re human, “we’re going to make mistakes, but we’re also going to find our way back to each other” (287) if the friendship is true.

Finally, Johnson reminds us to allow people to be their full, imperfect-but-still-worthy selves and to forgive ourselves of our own imperfections since we can’t all win the genetic lottery.

- Posted by Donna