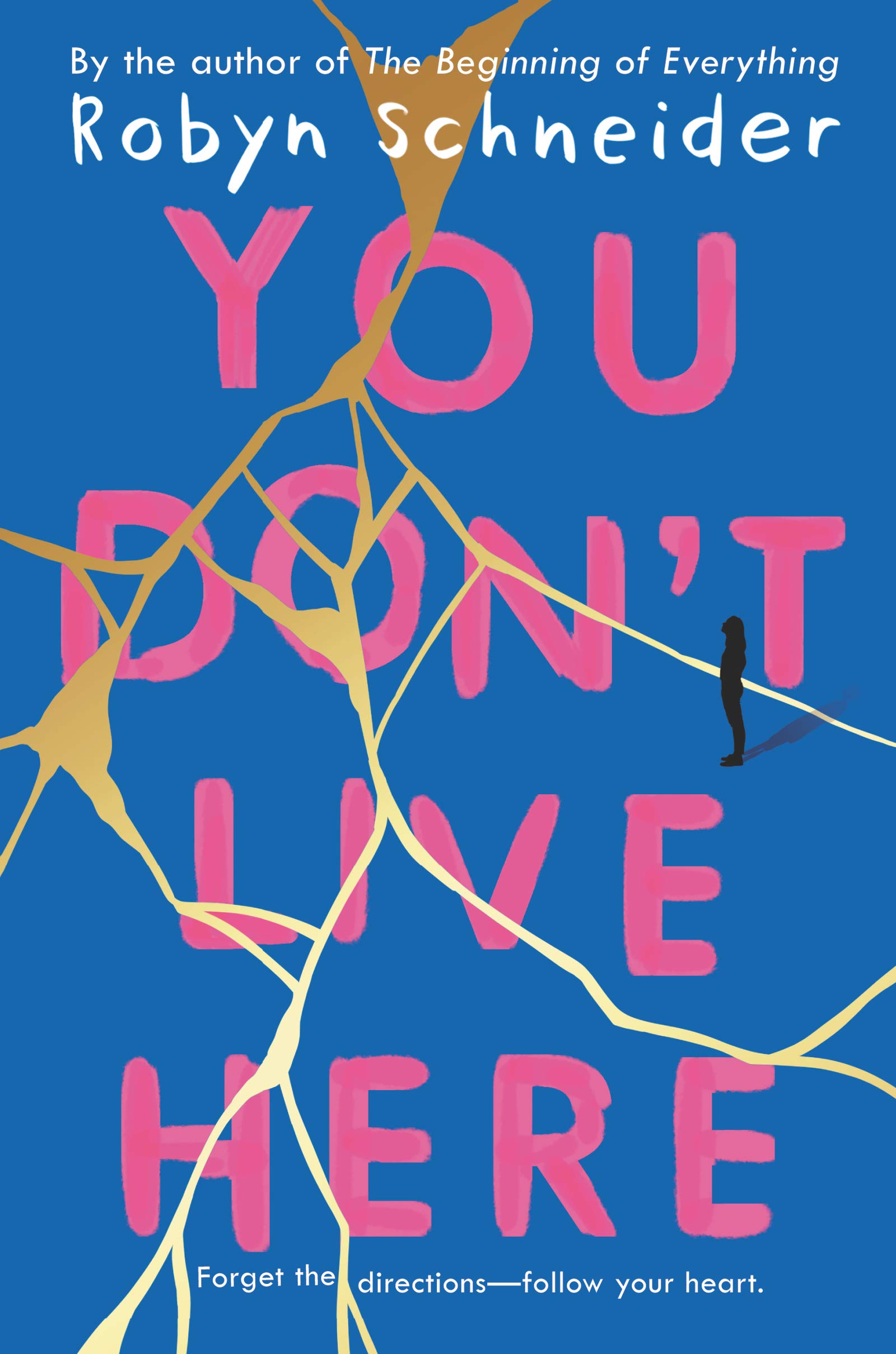

Reading You Don’t Live Here left me wowed and gushing that author Robyn Schneider is a genius at capturing the search for one’s true self! In her novel, Schneider not only shares insight into human nature and how keeping parts of ourselves hidden has consequences but includes multiple metaphors for the therapeutic power of art. I also laughed out loud when she referred to high school as a “uniquely hellish social experiment” (70).

Reading You Don’t Live Here left me wowed and gushing that author Robyn Schneider is a genius at capturing the search for one’s true self! In her novel, Schneider not only shares insight into human nature and how keeping parts of ourselves hidden has consequences but includes multiple metaphors for the therapeutic power of art. I also laughed out loud when she referred to high school as a “uniquely hellish social experiment” (70).

Sixteen-year-old Sasha Bloom is a photographer, an identity she gravitated towards after her mother bought her a camera because Sasha would rather be invisible behind a camera lens than be a continued target of bullies like Tara Angel. Now, rather than focusing on self-discovery, Sasha can capture the best angles and the perfect moments that belong to others.

Besides the search-for-self angle, Schneider’s book presents several powerful metaphors about art. Sasha loves photography because with the right angle and the right light, she can capture people exactly how they want to be seen instead of how they truly are. Their ugliness or sadness can be swept out of the frame.

But when an earthquake robs her of her mother, Sasha crumbles to pieces herself. Now a fragile, fractured teenager worried that she’ll wither away, Sasha stashes her camera and reads fantasy to fill her head with magic instead of monsters. Although her estranged grandparents take her in, Sasha feels more like a replacement for her mother while trying to be the girl her grandparents want.

Once the dazzle of her luxurious new existence at Baycrest High wears off and the desperation to please her grandparents wanes, Sasha realizes that she delights more in radical ideas and being ridiculous. Meeting Cole Edwards, who is the kind of attractive that needs a warning label, and Lily Chen, a bold, matter-of-fact girl, also plays a role in Sasha’s transformation.

Although Sasha is attracted to Cole, she eventually discovers that he is not boyfriend material. Just as she drew a banana in art class based on what she knows to be a banana rather than drawing the flawed and overripe fruit that is actually in front of her, Sasha trains her eye to do more than look quickly and assume.

Sasha also realizes that she says yes too often, agreeing with everything her grandparents want because she doesn’t want to rock the boat. She never stops to think that the boat might not be headed to a lighthouse but to a yacht club, which may be her grandparents’ preference but not her own.

Tired of faking and lying and misleading, Sasha breaks out of her shell, deciding that it is time for her to discover who she wants to be instead of allowing her grandparents to steer the boat.

Inspired by Lily’s bravery to be herself and fortified by her art teacher Mr. Saldana’s interest in her photography, Sasha decides it’s time to amend her behavior—she is determined to no longer live her life underexposed and off-balance. As she untangles the knots of her grief and edges closer to the person she is supposed to be, Sasha discovers that paints and charcoals might be worth learning—even if she’s not great at working with them. By adopting a different perspective, she begins to see that sketching is about working with shadows, while photography is about working with light. With drawing, she will need to create the negative instead of the photograph.

Sasha’s process of healing from her brokenness reminds Lily of the Japanese art of kintsugi—“the idea that neither damage nor repair are shameful. That actually they’re what makes these pieces unique, because without the broken pieces they’d just be ordinary” (209).

Supportive people act like the gold and the glue in kintsugi—knitting the broken pieces back together and returning beauty to life.

And then, Sasha kisses a girl, experiencing all of the electricity and excitement of kissing a boy. Confused but intrigued, she realizes she has lifted the lid on “Schrödinger’s box, containing two possibilities at once” (239).

The reader gets to accompany Sasha on this golden journey—from hiding and playing it safe to being ready to take a risk, be honest, and claim her identity as a bisexual teen. After all, Sasha knows from experience that disasters don’t only accompany risky behavior.

Although the novel ends true to life—with the unexpected—Sasha’s art project reveals her ability to stand tall despite her brokenness. Through a series of photographs, Sasha shows how the overall idea of someone isn’t actually the truth since who we truly are is often invisible. Explaining her exhibit to Lily, the girl who taught her to live her truth, Sasha says: “I wanted to play with the idea of how we curate versions of ourselves that are rarely honest. And how easy it is to forget that we don’t really know each other, [even though] we live in this social structure that presumes we do” (351).

- Posted by Donna