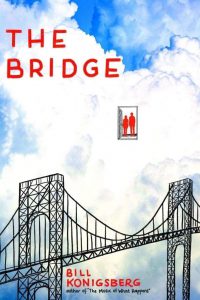

In an effort to share with readers the challenges faced by a person who endures the misbehavior of brain chemicals, Bill Konigsberg writes his novel The Bridge in a nonlinear form. Under the influence of his pen, the reader’s brain trips over itself, unclear and unsure of reality. Does Tillie Stanley—a girl with a beautiful, smart, funny, and magnetic personality—jump from the George Washington Bridge to drown in the Hudson River in New York? Does Aaron Boroff—a creative, friendly, musically-inclined seventeen-year-old with a sense of humor commit suicide? Or do both decide to put their broken lives back together? Just when the reader believes he/she has discovered the truth, Konigsberg picks up a plot thread that puts reality in a tangle as we travel down the path of what if?

In an effort to share with readers the challenges faced by a person who endures the misbehavior of brain chemicals, Bill Konigsberg writes his novel The Bridge in a nonlinear form. Under the influence of his pen, the reader’s brain trips over itself, unclear and unsure of reality. Does Tillie Stanley—a girl with a beautiful, smart, funny, and magnetic personality—jump from the George Washington Bridge to drown in the Hudson River in New York? Does Aaron Boroff—a creative, friendly, musically-inclined seventeen-year-old with a sense of humor commit suicide? Or do both decide to put their broken lives back together? Just when the reader believes he/she has discovered the truth, Konigsberg picks up a plot thread that puts reality in a tangle as we travel down the path of what if?

As Konigsberg takes us on this convoluted journey with his two protagonists, readers experience their anguish, sadness, let-downs, and humiliation. Because their brains make them think things that aren’t true, both Aaron and Tillie believe they are unfit for life; they don’t see what makes them gifted or gifts to the world. Yet, we can see the pleasure that they give and receive, just as easily as we cringe at the cruelty of Tillie being fat-shamed by her ex-best friend Molly Tobin, shunned by her father, and ghosted by Amir Rahimi. And just as easily as we slump in despair when Aaron’s mother abandons him or when friends share criticism, commit microaggressions, or forget to comment on his songs.

As Aaron realizes that because of his depression, he has sadness in his life, he comes to recognize that he also has happiness, “at random moments, and silliness, most of the time, and weirdness, just about always. His feelings are his. They don’t fit in a box and have a tidy label” (20).

Among some of the truths that Konigsberg tells about suicide ideation and about life, readers will find gems of wisdom and advice:

- Life can be considered difficult or easy; it all depends on your perspective; after all, “so much of life is how you approach it” (84).

- “Grief is hard. But here’s the thing about time: It doesn’t heal [all wounds], but it [does allow] you to reassemble your life around the wounds” (121).

- “Who takes a person’s trauma and makes it into a joke? Who does that?” (151)

- “Life is like a museum, and you have to curate” (175). Deciding what to display and what to keep hidden is a tricky business, and sometimes in the process, things get lost.

- It is a human desire to be seen and heard and loved; to feel a sense of belonging and to just “be enough.”

- To be different is an isolating experience until you realize that everyone is dealing with some brand of baggage.

- It hurts to be singled out or excluded for physical appearance, gender identity, race, or interests. “It’s maddening to be seen for one thing when we’re all so many things” (188).

Whether the two teens in their mental prisons can hold on for one more day is for the reader to determine. Nevertheless, we learn that people and love are both lifesaving and life-taking and that life is filled with hardship. While many of us perhaps haven’t wished for our lives to be over, we have definitely wished at times for them to be different. We further discover the magic in compliments and how connection and love provide antidotes to despair and devastation.

As much as Konigsberg’s style of storytelling frustrates the reader, it is from this frustration that we begin to understand the confusion of someone who endures depression. Some of the stories Tillie and Aaron tell themselves are true –life and people often don’t react in ways that we would like. This disparity leaves us feeling terribly alone, but when we look past the conflict, we begin to see that some of the narrative is just fiction and that life requires us to hold on for the miracle or it will never happen. We have to decide if we’d rather be real and made fun of or fake and safe. However, “the thing about [being real] is that people are cruel. And when you’re really real, and people critique that real, it cuts too deep. . . . Real is best when combined with craft” (287).

Besides making depression more understandable, The Bridge serves as a conversation starter about a difficult topic. According to Konigsberg, the more we talk about suicide, the more we demystify it. These discussions need to ensure they do not glamorize suicide nor present it as a solution to struggle. They also need to include the impacts and alternatives, not create suicide as some magical answer.

This is a book for anyone who has ever had suicidal thoughts or for anyone who has ever told a depressed person to “just get over it.” In the back matter of his novel, Konigsberg shares statistics and resources with a special focus on being an ally for LGBTQIA+ youth.

- Posted by Donna