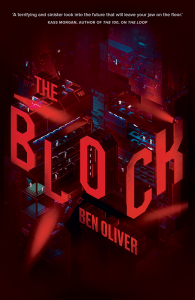

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley gets a major update with The Block by Ben Oliver. In Oliver’s second book in The Loop Trilogy targeted for young adults, readers will experience a video game vibe, like that achieved in The Matrix. Along with the characters, they will wonder what is real and what is simulated.

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley gets a major update with The Block by Ben Oliver. In Oliver’s second book in The Loop Trilogy targeted for young adults, readers will experience a video game vibe, like that achieved in The Matrix. Along with the characters, they will wonder what is real and what is simulated.

In this new dystopian world, everybody’s happy because Happy—an artificial intelligence—rules the world. Galen Rye is in charge, and he decides who suffers as a battery—without hopes, dreams, and ambitions as they power the world with their energy harvested from pain, fear, and anger. He decides who should be brainwashed into being the kind of person the world needs—placid, docile, compliant, and living in blissful ignorance in a virtual world called Purgatory.

Happy thinks of humankind as a virus, so it is “repairing the broken species, destroying a diseased batch and starting anew” (288). In order to maintain control, Happy uses technology, tricks, and tactics like fear, coercion, bargaining, and confusion to manipulate people in getting them to turn on one another. For example Luka knows where the Missing are but refuses to tell, even when Happy tries to scare the location out of him with an apparition of his mother.

Just as Huxley refers to various castes of people, Oliver introduces Smilers, Clones, Alts, and Regulars. In fact, with their perfect features and bodies, “all of them with their enhancements, mechanical lungs, robotic hearts, and synthetic blood,” (154) the Alts remind me somewhat of the Uglies series by Scott Westerfeld.

Sixteen-year-old Luka Kane and a number of his friends rebel against this technology. They are willing to die for life, evolution, dreams, and love. One of those friends—perhaps the most valued member of the team—Pod has a visual impairment. Through the actions of this group of young people, Oliver encourages us all to ask important questions about greed and a thirst for dominion—about whether equality is an impossible ideal when “those with power hold on to it with viselike grips” (210) and push the underprivileged into the dirt.

Another question to ponder: What does it mean when rebels are being killed for trying to stand up against Happy’s plan to eradicate the world of humans” (84)? As this mass genocide transpires, the reader will likely wonder along with Luka: “I cannot understand how so many people can be talked into believing in something so cruel, something so ruthless and vicious” (157). From this wondering, Luka decides that we cannot justify evil means with a virtuous end nor can we justify genocide with a better future. He says: “I still believe in humanity, I believe in the goodness of people, and I believe that bad people can change and see the error of their ways. The moment I stop believing in that is the moment I stop fighting” (296).

Another truth surfaces when Galen talks about the need for suffering in the name of progress. In response, Luka points out that when we look at data and not at individuals, understanding will escape us. We can’t look at humanity as one entity or as a uniform species. Each one of us is different and unique, working toward distinct goals. “To wipe us out based on the sum of our parts is to erase the unfathomable beauty that resides in most people” (298). That beauty surfaces in creativity, ambition, talent, and the capacity to love. Perhaps the book’s best moral comes when Oliver writes: “We cannot look down upon the accomplishments of others simply because we do not share the same aspirations” (303).

Regrouping with some of his ethnically diverse rebel friends, Luka continues his mission to take down Happy, the government’s operating system. In addition to fighting madness—a unique kind of suicide—the group encounters a multitude of other obstacles—like Ebb, Deleters, Mosquitoes, and vengeful people like Tyco Roth.

- Posted by Donna