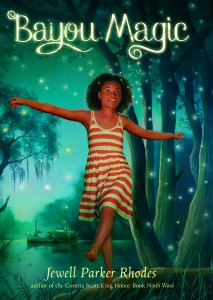

The quiet calm of the wait and the comfort of savory smells make cooking a favorite activity for Maddy, the protagonist in Jewell Parker Rhodes’ recent release, Bayou Magic. Although she was born Madison Isabelle Lavalier Johnson, Maddy is often called Bird Bones because she is small and thin. At ten years old, Maddy is not yet comfortable in her own skin, and she wonders why she sees the world differently than her four sisters do.

Maddy prefers listening, watching, and dreaming. Now it’s her turn to have a bayou summer, and her sisters, who each took their turn, warn her of all the drawbacks of a bayou visit and even try to frighten her with taunts and teasing: “Grandmère’s a witch. . . . I’ll never forget you . . . if the swamp swallows you” (4).

Used to “a world tamed by glass, metal, and concrete” (92), Maddy is overwhelmed by how immense and different the world is beyond New Orleans as she travels into the country, over the hills and through the woods to Grandmère’s house. At first, she is uncomfortable with the strangeness and difference she sees in the bayou, but as time passes, the thick, heavy air drapes about Maddy like a shawl and she doesn’t want summer to end.

Maddy finds similar comfort in Grandmère’s routines and stories. Grandmère teaches Maddy the power in listening, of paying attention to signs. Looking for signs and reading her surroundings like her Pa reads the newspapers, Maddy experiences the bayou with all its colors, abundant wildlife, rich diversity, and natural uniqueness. While harvesting herbs, gathering eggs, and exploring nature, Maddy discovers a love for the land and realizes that “nature isn’t just a picture in a book, or locked behind glass in an aquarium, or caged in patches and pots in a botanical garden” (125). Under Grandmère’s tutelage, Maddy learns to call fireflies and to “leave space for imagination” (138); she gradually recognizes that dreams and feelings and intuition are all ways of knowing and understanding the world.

Furthermore, she learns that stories, both real and imagined, are powerful. In Grandmere’s stories, Maddy confronts the sadness and ugliness of the slave trade and what it means to lose hope. These stories—and those about Mami Wata, goddess of the water—provide a means of connection, of preserving history and memory, of engendering cultural pride for Maddy, who spends her summer searching for Mami Wata so that she can solve the mystery of the existence of mermaids.

In the bayou, Maddy also befriends Bear, the nicest and strangest boy she knows, and in his dirty, strong, calloused, and capable hands, she goes on adventures in the swamp—by air boat and by foot. On their explorations and from her experiences and encounters, Maddy discovers that she has “sauce,” that she’s “tiny mighty,” just like her grandmother. The bayou and the adventures it offers both influence and shape Maddy’s identity.

When Grandmère asks Maddy who she wants to be when she grows up, Maddy responds, “A hero. . . . I want to be good. Be brave.” But to be a hero means bad things have to happen, and Maddy isn’t sure she’s up to the challenge. After all, “saving the environment is harder than fractions. Harder than getting [her] sisters to be nice. Harder than dreaming nightmares. Or searching for mermaids” (122). Speaking out for a friend being bullied is equally difficult.

For teachers looking for a book to meet the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), Bayou Magic will fill the bill. According to the CCSS, students who are college and career ready understand other perspectives and cultures, and Rhodes wrote this book in part to celebrate the culture of the Louisiana bayou with its Creole cooking, swamp customs, and snappy, staccato, bouncy Zydeco music. She also raises questions to increase awareness about environmental issues. Her book enables teachers to expose students to multiple perspectives, to situations that encourage a critical stance so as to inspire wisdom that might lead to an improved way of living in the world.

For readers who enjoy books written by Sneed Collard (Double Eagle, Dog Sense), Carl Hiaasen (Hoot, Flush), and Jean Craighead George (Charlie’s Raven, Frightful’s Mountain), Bayou Magic will likely bring pleasure.

A curriculum that includes books by these authors invites students to decide for themselves what action, if any, is appropriate to take in closing the gap between the ideal and the status quo. Reading books with an environmental theme gives students a chance to develop a body of knowledge about modern environmental conditions and to critically examine the culture that created those conditions. Whether curriculum should stop at intellectual understanding of social problems or include an action phase is a question for local contexts to resolve, but in the words of the Lorax, “Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

Just like the Lorax gives voice to the trees who have no tongues, “tiny mighty” Maddy gives voice to the bayou with its gators and glimmering fireflies, its pelicans and plant life.

- Posted by Donna