Fluent in the language of vectors and the laws of physics, Rukhsana Ali dreams of one day working at NASA and plans to attend Caltech when she graduates from high school. She also can’t wait to escape her home in Seattle where her Muslim parents believe that daughters and sons are not the same.

Fluent in the language of vectors and the laws of physics, Rukhsana Ali dreams of one day working at NASA and plans to attend Caltech when she graduates from high school. She also can’t wait to escape her home in Seattle where her Muslim parents believe that daughters and sons are not the same.

In her mother’s mind, Rukshana’s worth in the marriage market is directly proportionate to her culinary prowess. Therefore, she has to know how to prepare chai, goat vindaloo, and roti in order to impress a potential mother-in-law. But Rukshana isn’t a traditional Muslim, and she’s more interested in Ariana’s sweet-nothings whispered than in learning how to make laddoo. When Ariana nuzzles her ear or kisses her neck, Rukshana’s body tingles from head to toe.

Afraid that her revelation that she is a lesbian will ruin her family and her life, Rukhsana keeps that part of her identity secret. Although she realizes that Ariana deserves better than a deceitful partner who is unable to fully embrace her publicly, Rukhsana begs Ariana to wait until they are safely in California.

Even though Rukhsana’s parents Ibrahim and Zubaida are Bengali people renowned for their love for food, poetry, and music, they are also known to be homophobic, parochial, and protective. Regarding Rukhsana’s progressive attitude about education and gender equality, Zubaida tells her daughter: “You have the power to honor our family’s good reputation. But if you’re’ not careful, you could also be the one to stain it. And it is my obligation to make sure that does not happen” (5). Despite their differences, Rukhsana doesn’t want to hurt her parents. She knows that their rules come from a place of love and that they have just been raised with a different set of beliefs.

However, when Zubaida walks in on Ariana and Rukhsana and discovers the two girls kissing, she slaps Ariana and banishes her. She also tells Rukhsana that she is sick and disgusting. Shocked by her mother’s abusive and caustic response, Rukhsana wonders how family can be both vicious and loving.

Afraid that her daughter has been possessed by a jinn, a supernatural spirit thought to be prone to evil, Zubaida whisks Rukhsana off to Bangladesh under the guise that her beloved Nani, her grandmother, is ill. Once there, Zubaida sets out to exorcise the demons from her daughter and to shame her into being straight. Rukhsana wonders just how far her parents will go with their narrowminded and extremist views.

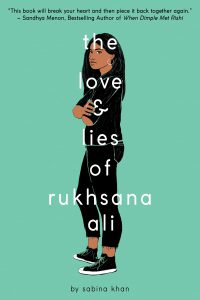

The reader will likely find several other human truths revealed in Sabina Khan’s novel The Love and Lies of Rukhsana Ali—both the frightening and the somewhat familiar. Although Rukhsana herself lives a lie, she is also the victim of deceit and emotional blackmail. Furthermore, being dark-skinned, Rukshana has to deal with the disconcerting feeling of those who see her as their “brown Muslim friend” and regard her with some measure of suspicion. But, she also has to confront her own biases.

Khan’s novel is steeped in Bengali/Muslim culture—from the foods and customs and religious conviction to the language, rituals, and family practices. Khan shares with readers details about the Muslin festival named Eid, the intricate henna designs of mehndi, the Hindi cinema called Bollywood, and Bengali fashion: bangles, saris, and kurtas. It is also a heartbreaking story about love and acceptance in the face of great fear and challenge. Finally, readers get a glimpse at what acceptance and understanding might mean when confronting prejudice—that sometimes we need to embrace the parts of others that are different, not just the parts that we share.

From Nani, Rukshana learns that we must be the masters of our own destinies. Sometimes that mastery requires fighting to take back control of our lives, and sometimes it means we will hurt the ones we love the most. As Rukhsana reads her grandmother’s diary, she discovers the depth of abuse Nani endured and wonders how she was able to remain so strong. Nani tells her granddaughter: “Sometimes the love you have for others can give you a tremendous amount of strength” (195). Rukhsana finds this love in her brother Aamir, her cousin Shaila, and her multiple friends.

This is an important book, not only for its cultural enrichment and its lessons on human nature but for its perspective on difference. Rukhsana refuses to allow her parents to reduce her existence to something that can be controlled by others: “I was who I was, and I would not be erased” (214). Readers also recognize how reconciling the different elements of identity can be ridiculously difficult but necessary to a sense of well-being and wholeness.

- Posted by Donna