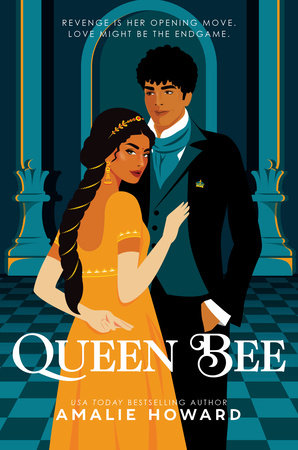

An Earl’s daughter, Lady Ela Dalvi doesn’t fall from grace; she is shoved by her former best friend, Poppy Landers who concocts a tale that sullies Ela’s reputation. Vowing to get revenge, Ela invents a new personality and becomes Miss Lyra Whitley, an enigmatic heiress who plans to infiltrate the glittering ballrooms of London, 1817. After all, “money has a way of opening the tightest, most elite circles” (10), and the recipe for high society female accomplishment in the United Kingdom during the late Regency era and later were fortune, connections, beauty, and virtue.

On this defiant journey across class boundaries, Lyra’s disguise seeks position, influence, and power. Her target is a mistress of slander, and Lyra plans to take her down in a five-step revenge plan. In Lyra’s mind, revenge can be likened to chess. Both are games of strategy, patience, and positioning. Lyra plans to take down the queen and checkmate the king.

Although she is well-aware that war is not won without casualties and that popularity is both fickle and fleeting, Lyra doesn’t plan on a mutiny from her heart. Once in motion, all of the moving parts of the plan, as well as the shifting alliances, are difficult to predict. Soon, her convictions begin to feel like they are built on quicksand. Because Lyra can’t reconcile the girl she had been and the girl she has become, she wonders if it is possible to lose herself entirely while pretending to be someone else. As Ela’s memories and feelings undermine Lyra’s purpose, her brain grows muddled and her heart gets tangled by Lord Keston Osborn’s flirtations. Lyra is intrigued by Keston, “and intrigue is a dangerous thing. It can send a mind off course, shake a plan from its path, [and] leave chaos in its wake” (104).

To write her novel Queen Bee, Amalie Howard takes on this history to write a romance novel fit for a queen. In the process, she also takes up the topic of gender roles. “In a lot of places, not just England, males had their power and females had their wits. The goal of any highborn girl was to marry well. We were bred for that. Our wombs held value, not our brains” (54).

Given this reality, Lyra wages her battles in subversive ways in order to convey a message about maintaining power and having agency while being compassionate and considerate. She tells her friend Rosalin: “It’s true that we women live in cages of society’s making, that we are bound by the rules of our station. But we are not prisoners! We have our own minds and our own dreams, and if we give up on those, then we’re the ones who lose” (187).

Tucked within the novel’s pages, the reader will also discover several significant life lessons:

- “The best way of avenging thyself is not to become like the wrongdoer” (147).

- Even though we all deal with pressures and expectations to “perform and conform,” if we continually shove aside our dreams for the sake of duty, the consequences can be dire.

- “People aren’t kind because they expect anything in return. They’re kind because it makes them better people” (156).

- Losing is a matter of perspective.

- “When a person behaves badly, their ugliness comes from them, no one else. We can only control ourselves. . . what we do” (202).

And the truest moral of them all is that we don’t get do-overs in life; we only get to do better because life is a “series of moves and countermoves with an uncertain outcome” (343).

- Posted by Donna