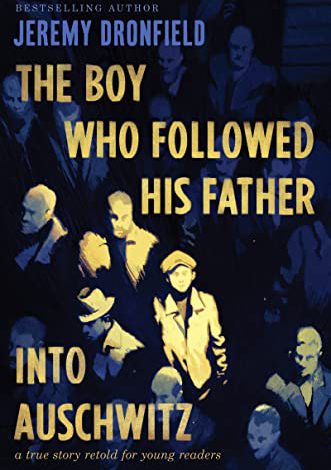

Although The Boy Who Followed His Father into Auschwitz by Jeremy Dronfield is “another Holocaust book,” this nonfiction account retold for young readers reminds us all how vitally important it is to remember what happened “in those terrible years” (301). So as to brand their minds and inspire young readers to do whatever they can to ensure that nothing like the Holocaust ever occurs again, Dronfield captures the story of the Kleinmann family with a focus on Fritz, who is fourteen years old when the novel opens, and on Kurt, who is eight.

By personalizing the tale so that readers can form connections, Dronfield builds empathy and inspires social justice. Kurt, a young boy who gains the German nickname Spitzbub (rascal), is reassured by music. He lives with his Jewish family in Vienna, Austria, where he runs in Karmeliter market, climbs lampposts, sets off caps to confound the pigeon catcher, and plays Ping-Pong with his father and brother. Filled with the carefree nature of his childhood, Kurt especially enjoys helping Mutti coat the veal cutlets for Wiener schnitzel on Shabbos and the chess games and family time that follow.

Fritz, too, spends his summer evenings kicking a rag soccer ball around, laughing and chattering with his friends, and getting cream cakes and pink wafers from the various stall owners set up in the market.

All of this comes to an abrupt halt when Hitler’s Army invades Austria and sets in motion a wave of hate-motivated devastation. The family is separated, and Fritz and his father, Gustav, are sent to a labor camp. Despite the horror, there are heroes in this tale: Robert Siewert, Alfred Wocher, Samuel Barnet, and even Fritz and his father, to name a few.

Through an epic act of faith as they are shuttled from Buchenwald, Auschwitz, and Mauthausen, Fritz and Gustav cling to hope. However, as the days and weeks and years go by in each of these places of suffering where danger and death are part of everyday life, it gets harder and harder for Fritz to hold on to hope or to believe the lie that “Work Brings Freedom.” Fritz sees terrible things that no human being should have to see, let alone a boy his age: Men tortured for not working hard enough, men killed, men left to die from injury, illness, malnourishment, and disease, people tormented and robbed of their dignity. “Auschwitz took good people and made them so that the best they could hope to do was survive and help the people closest to them” (240).

There is something mortifying about reading a Holocaust book. Although seeing the darkest depths of human cruelty alone is deeply unsettling, realizing that people endured in the face of such racism is equally shocking. I don’t have a frame of reference for such hate-motivated mass extermination nor for the survival instinct of those with daring and a hope that won’t die. I don’t hold culpable those who sought out false comforts or had to make difficult decisions to survive. Such books denounce cruelty as well as celebrate the spirit of prisoners who refused to succumb to the SS, even when they were beaten down and tortured—all because they didn’t look like those in power or share the dominantly held beliefs. But what lingers, long after the reading is a feeling of sadness and angry indignation: How could this happen and how do we prevent it from ever recurring?

- Posted by Donna