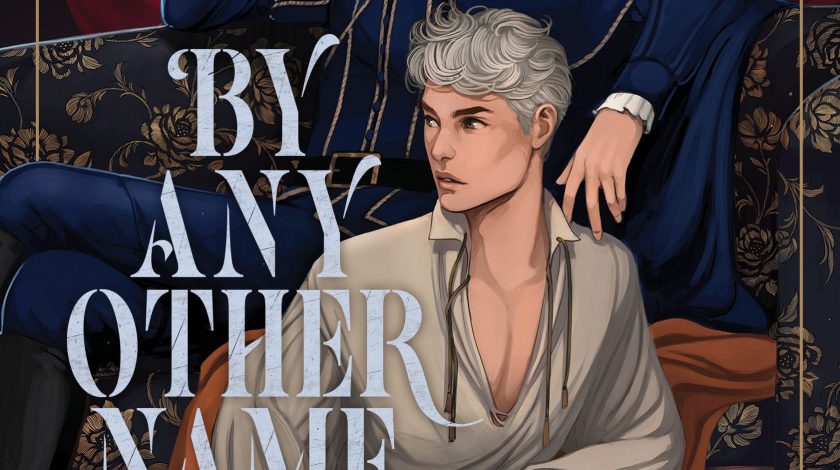

With By Any Other Name, Erin Cotter writes a historical fiction novel about William Shakespeare’s London, sharing ample allusions to his work and plays. The story opens in 1593 London at the Rose Theater, where young Will Hughes is aging out of the theater because his voice is changing and he will no longer be able to play the female parts. To further complicate his life, the plague is making its way through the city, and theaters will close until it passes. As a result, his patron, Christopher Marlowe (Kit) encourages him to find another home.

Home. The word makes Will’s breath catch. At eight years old, he was abandoned by his family, who couldn’t afford to feed the extra mouth and sold him to two strangers who promised him safety and an education but instead sold him into indentured servitude like a mule. Human trafficking was a lucrative practice in 1593, but Will manages to slip away and shimmy out an open window. Although Will was taken from his family as a burden, he plans to “return to them a blessing, richer than anyone they’ve ever known” (22). Hence, he has been working and stowing money ever since and plotting some kind of revenge against the queen he hates. After all, “tis hard to harbor love for the queen who allows her men to take sweet-voiced boys from their families and force them to entertain in cities” (29) or who sends her soldiers into the country to steal land from the commoners, burning their homes and ending the idea of common lands for grazing while branding those who fight back as traitors.

However, a mystery unfolds when Lord James Edmund Bauffremont of Bloomsbury invites Will to manage his illegal theater. Soon after, Kit is murdered as he attempts to protect Will. Believing he owes Kit the dignity of discovering the reason behind his death, Will makes it his mission to find answers to all of the secrecy. What he discovers is far shadier than he imagines. But, Will’s heroic streak is not to be denied.

Bloomsbury, too, is keeping secrets “like a locked treasure chest, and the more he hints at what’s inside, the more [Will] wants to pick the lock and learn for [himself] what riches he keeps hidden” (100). One discovery reveals James’ motive for thwarting the queen. Witty, generous, optimistic, and idealistic, James wishes to use his station to undo some of the harm done by those seeking solely to preserve their noble names and stuffing their coffers. However, as Will learns, “there’s no certain method to uncover a man’s secrets. And secrets are far deadlier and more pointed things than blades” (372).

Cotter’s book not only offers a murder mystery filled with spies, heroes, love, courage, and intrigue, it also provides commentary on human nature and helps the reader to see how much about society still remains unchanged since the last 1500s. For example, when the rich and powerful want more of something, they rarely stop until their prize is won. Will is motivated to banish fear, uncertainty, and poverty, but will those ambitions mean he goes from player to puppet and bait in an assassin’s trap?

Other topics pursued by Cotter include how people care for things they can’t understand, how we’re drawn to love even in the most impossible of situations, and how we will often wonder, in our self-serving endeavors, whether we have enough goodness in us to be worthy of affection. We further wonder how far away we might have to travel to escape laws and politics to live the life we desire. From the lives modelled by Will and James, readers might be inspired to create our own place instead of accepting the cramped space the world offers us.

Cotter also asks tough questions: “Is pride truly such a valuable thing that it’s worth killing over? Can pride feed you, clothe you? Make you feel as though life is worth living” (334)? And how many more people will be hurt or killed before we learn the complicated answers?

Another point of contention is the writing of history, which is often “a patchwork of whispers and murmurs which buries the single scrap of truth so deep that none can recognize it” (408). Often, we tell lies, but sometimes “a lie is not a lie but a fiction we must tell ourselves to make life bearable. To move on instead of staying stuck forever in what-could-have-beens” (414).

If her book does nothing else, Cotter shares this important truth: that we humans all carry pain in our own way and do not speak of it. Rather, we “live around the shape of people who used to be in our lives. We go on because the only other option is to give up” (421).

- Posted by Donna