Olivia (Livie) Mead trades safety, comfort, and normalcy for a rare and enchanting adventure on her seventeenth birthday, October 31, 1900, when she participates in a women’s suffrage rally. Later that night, in the spirit of a good Halloween fright and under pressure from her friends, Livie agrees to subject herself to hypnosis and experiences the utter bliss of deep relaxation. Henri Reverie, the hypnotist, tells Livie that because of her birth date, “legend says you are a charmed individual. You can read dreams and possess lifelong protection against the spirits” (9), but from that night onward, Livie’s life changes drastically.

Olivia (Livie) Mead trades safety, comfort, and normalcy for a rare and enchanting adventure on her seventeenth birthday, October 31, 1900, when she participates in a women’s suffrage rally. Later that night, in the spirit of a good Halloween fright and under pressure from her friends, Livie agrees to subject herself to hypnosis and experiences the utter bliss of deep relaxation. Henri Reverie, the hypnotist, tells Livie that because of her birth date, “legend says you are a charmed individual. You can read dreams and possess lifelong protection against the spirits” (9), but from that night onward, Livie’s life changes drastically.

Livie’s father, the infamous Dr. Walter Mead, finds out about his daughter’s rally indiscretion when a potential patient will not trust the Portland dentist with his mouth when he can’t even control his own daughter. Hoping to make her silent and submissive, a woman of fine manners and strict obedience, one “who understands her place in the world” (37), Dr. Mead wants to free his daughter of “unladylike dreams” and marry her off to Percy Acklen, a man of means and money. Despite Livie’s insistence that she isn’t interested in marriage and that her mind isn’t easily removed like a rotten tooth, Dr. Mead hires the mesmerist to cure Livie of female rebellion. Although Livie fears that Reverie will take away her free will, rob her of thoughts, kill her imagination, and remove the burden of “impossible dreams,” what he does is make her ultra-aware with an enchantment: “You will see the world the way it truly is. The roles of men and women will be clearer than they have ever been before” (64). Whether a gift or a curse, now Livie hallucinates and can no longer articulate her anger and distress, which are silenced by the phrase, “All is well.” She sees men as vampires and women as fading, oppressed, caged, and ruined.

Wishing for the world to return to normal, Livie begs Henri, whose real name, is Henry Rhodes, to give her back her voice and her old view of the world, but Henry confesses that he only acted out of desperation because he needs the money for his sister, Genevieve who has breast cancer. Unwilling to accept the world as it is, the two decide upon a partnership and a plan they hope will fool the doctor, save Genevieve, and free them both from Dr. Mead’s oppression. Livie’s post-hypnosis sins include bicycling, kissing, and getting “drunk on moonbeams and speed and the incomparable exhilaration of hanging on to another person as if one’s life depended on it” (238).

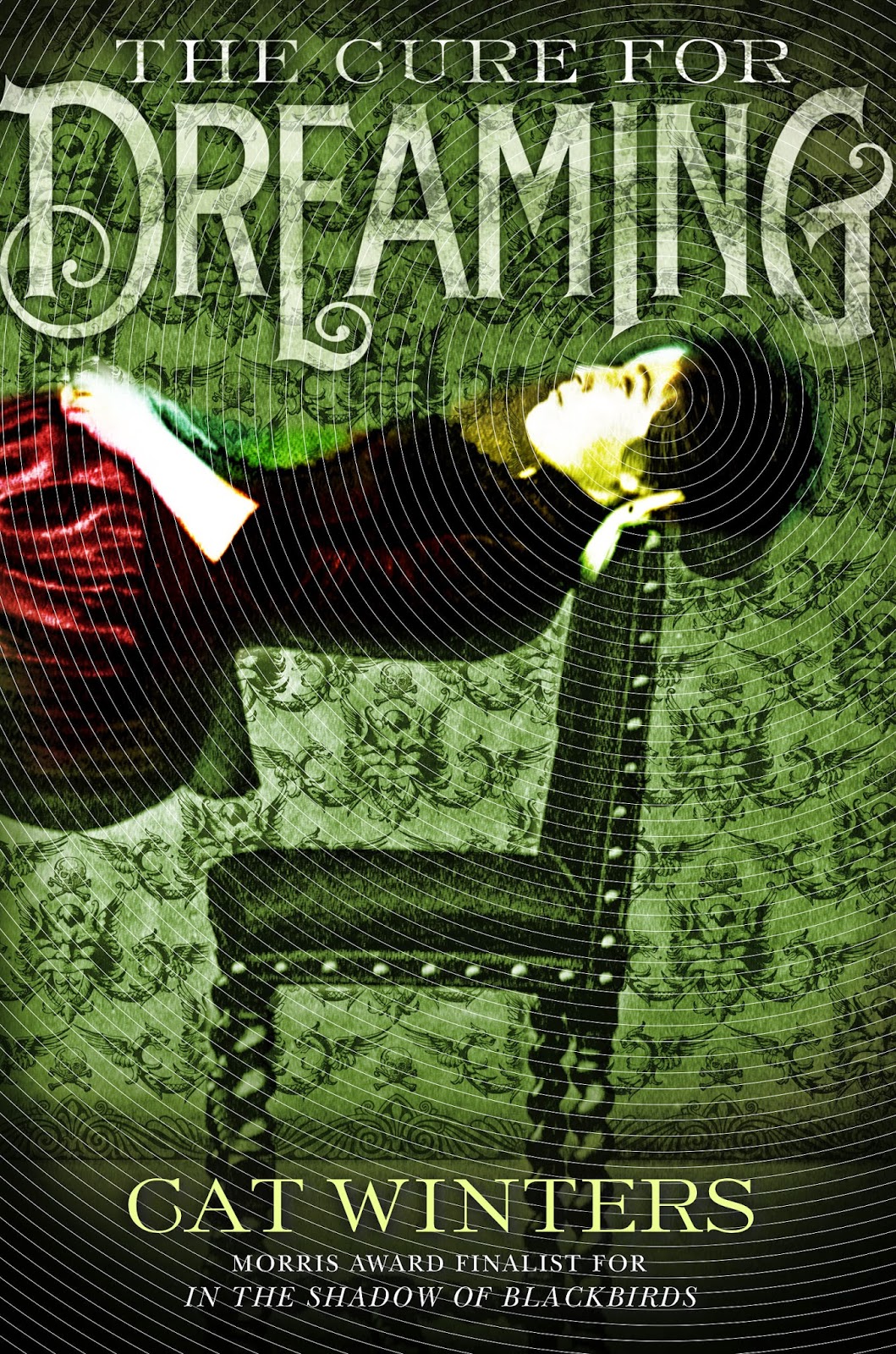

Cat Winters writes The Cure for Dreaming with an imagery richness that favors vivid colors. She also sprinkles quotes from the time period that lend authenticity to the text, making this historical fiction accessible to young adult readers. Winters captures a time in history when men believed that women belong in the home and that only desperate and unfeminine women take additional jobs. To combat this oppressive and narrow view, Winters memorializes women who fought against political slavery: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Abigail Scott Duniway, Susan B. Anthony, and Carrie Nation. She further celebrates authors who questioned the subordination of women: Kate Chopin, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Mary Wollstonecraft. As Livie’s story unfolds, Winters extends gratitude to all men and women who fought to end inequality. Her book ensures that those who sacrificed and struggled to give the silenced a voice would not be forgotten. To the end of her novel, Winters not only appends a chronology of “When and Where U.S. Women Gained Full Suffrage” but also provides a list of recommended titles for further reading on the topics included her novel: women’s rights, the suffrage movement, early dental practices, hypnosis, and Portland’s history.

- Posted by Donna