Nervy but not nuts, Buck Anderson craves adventure. Most comfortable surrounded by rock and roots and earth, Buck’s passion is caving. And living in southwest Virginia in the Appalachian foothills, this stubborn, risk-taker has many opportunities for discovering, exploring, and hoping to make history. When his best friend David Weinstein moves away, thirteen-year-old Buck loses his cautious cave-exploring partner, and “the first rule of caving is never—not ever—do it alone” (2).

Nervy but not nuts, Buck Anderson craves adventure. Most comfortable surrounded by rock and roots and earth, Buck’s passion is caving. And living in southwest Virginia in the Appalachian foothills, this stubborn, risk-taker has many opportunities for discovering, exploring, and hoping to make history. When his best friend David Weinstein moves away, thirteen-year-old Buck loses his cautious cave-exploring partner, and “the first rule of caving is never—not ever—do it alone” (2).

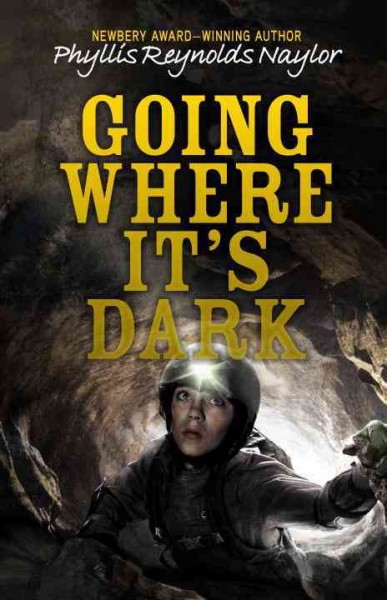

Although Buck disobeys this rule more than once, his fascination with caves and their potential danger is only one strand of the plot in Going Where It’s Dark by Newbery Award-winning author Phyllis Reynolds Naylor. Naylor, who often writes about the aspects of culture that challenge us, focuses on the roles that exceptionality and geographical circumstances play in one’s life. Because Naylor’s book embodies an artistic expression of the differently abled experience for adolescent audiences, the book deserves a look by the Schneider Family Book Awards committee.

“Going down in a hole where he might possibly be trapped was scary” (196), but Buck’s decision to tackle his stuttering by secretly engaging in therapy with Jacob Wall, a weathered and worn, former military speech pathologist, is “a different kind of dark” (196). Afflicted with rheumatoid arthritis, Jacob’s mobility is compromised, so Buck does small chores for him in exchange for five dollars a week. Buck’s motivation is not charity or compassion but a desire to buy a headlamp for his caving expeditions.

Buck, who avoids phone conversations and detests speaking in front of class because of the pity and humiliation it produces, doesn’t understand why he has been denied the gift of speech—a basic ability of being human. Having endured sessions with speech therapists, referrals, and various futile interventions, Buck has exhausted his efforts to speak with fluency and ease; the harder he tries to avoid stuttering, the more the words clog up his throat. Buck also confronts bullies who mock and heckle and jeer: “He’s so short his words get stuck in his windpipe” (31). Even his family members—who don’t want Buck’s stuttering to hold him back—explore cures: a twelve-day stuttering program in Norfolk, electronic devices, more effort, and a faith healer. Buck resists this chastising form of attention and wonders whether he’s weird, diseased, or broken. Thinking that he’s letting the family down or causing undue worry if he doesn’t stop stuttering puts a lot of pressure on Buck, who begins to hate himself and to question the fairness of his challenge with speech—the facial contortions, jaw clenching, shoulder shifting, blocking, and eye blinking.

Exasperated that “normal people [can] open their mouths and say anything at all without a problem” (62), Buck is intrigued when Jacob invites him to “think for a minute what [his] life would be like if [he] lost your fear of stuttering” (106). Through a series of jaw flapping exercises, sessions with a mirror, and “giving me the finger” (182) games, Buck learns to accept that he is not a stutterer, just a guy who happens to stutter. Buck also teaches Jacob a few lessons about “running backwards” and about how the choices we make can cripple us.

Although Naylor’s book revolves around the challenges Buck experiences with his normal disfluency and with the bully Pete Ketterman, Buck’s fascination with caves remains central to the plot. While some readers may not share Buck’s enthusiasm for trilobites, stalagmites, rock galleries like Luray Caverns, and stalactites or may not savor the notion of climbing, crawling, slithering, rolling, and squirming in a tight space, we can all relate to how passion and desire drive us—whether we seek the thrill of caving or of travelling the world. And we can all learn from one of the book’s most important lessons: What is easy for one person may be hard for another.

Art’s power to influence the human condition is another message. Both Buck and his twin sister Katie find liberation in art. For Buck, communication is fraught with challenges, but important, so he draws cartoons of The Life of Pukeman. Buck uses the cartoon frames not only to work through his anxiety and his anger but to build his confidence and to communicate his thoughts and wishes and dreams. While Buck’s cartoon strips serve as a method for tapping his courage and reclaiming his power, his sister uses her art as a creative outlet. In addition to drawing, Katie writes, tries out for plays, enters contests, and designs houses, parks, and malls. Through art, the two teens practice self-discovery and risk-taking.

- Posted by Donna