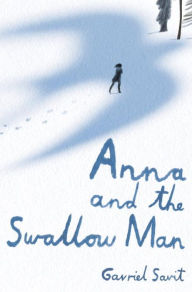

Set in 1939-1943 in occupied Poland, Anna and the Swallow Man by Gavriel Savit tells the difficult story of growing up during the Second World War, a time rife with barking dogs, tank invasions, bullying soldiers, fiery sacrifices, and other acts of hate and genocide. In 1939, Germans occupied Kraków with the sole purpose of purging the city of its intellectuals an d its academics. As Germany pushed in from the west, the Soviets closed in on the east. The occupation of Poland has been called one of the darkest chapters in the history of World War II since it marked the beginning of the Jewish Holocaust when almost eighteen percent of the Polish population was decimated by mass execution, forced eviction, and enslavement.

d its academics. As Germany pushed in from the west, the Soviets closed in on the east. The occupation of Poland has been called one of the darkest chapters in the history of World War II since it marked the beginning of the Jewish Holocaust when almost eighteen percent of the Polish population was decimated by mass execution, forced eviction, and enslavement.

Before his disappearance, Anna’s father, a professor of linguistics, fosters in his daughter a love of language similar to his own. For the Łanias, living in the world meant discovering something new diurnally, and every day of the week was experienced in a different language. For Anna, words evoked memories of people or other fond associations; for example, “every word of Armenian smelled like coffee” (3). Among its many lessons, Savit’s book reveals the truth that language is tied to identity and helps to define a person. To know many languages, then, gives a person multiple perspectives for experiencing the world.

Until her seventh year, life for Anna was built around memories of perpetual warmth and sun, public parks and gardens, cookies and coffee. But when war descends on Poland, that vibrant and happy life dissipates like vapor to be replaced by foreboding. War is a heavy word in any language, and while Anna is unsure of its full meaning, it seemed mostly “to be an assault on her cookie supply” (9).

When her father disappears, leaving her alone it the world, she translates confusion in the only way she has learned, by listening to language and by reading people. Anna had developed a habit of understanding strangers by comparing them to known acquaintances—“as if she were translating the unfamiliar phrase of each new human being using her full, multilingual range of vocabulary” (32). When she meets the Swallow Man, he is a pillar of defiance, excitement, energy, and brilliance with the skill to summon swallows. Because the Swallow Man also conjures images of her father, Anna follows him out of the city and escapes Sonderaktion Kraków.

The plot trudges along in the footsteps of seven year old Anna Łania as she traverses across Poland’s countryside with the mysterious Swallow Man as her guide. Besides his gift for talking in the language of birds, the Swallow Man speaks in metaphors as he imparts his lessons to Anna: Bears are Russians, Wolves are Germans, and knowledge is a weapon. Accompanied by observation, patience, and time—the Swallow Man tells Anna—knowledge will prevail against rifles. Their walking becomes a metaphor for survival, and the bird—which swoops and soars and sings—a metaphor for intellectual freedom.

Savit’s historical fiction account is captivating and compelling as it treks through this horrific time in history, as Anna picks the pockets of the dead and visits mass graves to pilfer in the name of survival. Besides having to discard the notion of human dignity, Anna’s innocence is further tested by other acts of human cruelty, and she learns the value of insufficiencies, “Anything is always better than nothing” (109). Employing a military strategy known as the blitzkrieg, which means lightning war, armored German tanks continue to advance across Poland, destroying everything in their path. Amid the death, destruction, and grimness left in their wake, Anna miraculously still finds joy, song, and hope. Although the face of death tests Anna’s kindness as war reveals its many ugly truths, Anna learns to ignore the transformations of elegance into battered chaos. Even when the prospect of death seems wonderfully seductive and she feels empty, Anna keeps putting one foot in front of the other; she walks on, hating the cruelty of the world too much to let it beat her. It is this sheer will-power and her desire to know why that are most admirable in Anna. Although once she starts asking questions, her innocence is lost, Anna reminds us that asking questions is the source of all knowledge.

Motivated by curiosity and a desire to know, Anna searches for meaning in the incomprehensible acts of war. Through Anna, Savit teaches readers that the why question fuels the brain to explore understanding and awareness so as to get to the root of discovery. Reflection involves looking back over what has been done so as to extract meaning, meaning that will enable a person to deal intelligently with future experiences. Essentially, reflection produces a transcript from which ideas can be retrieved and converted into learning. Anna’s passion for curiosity is the superpower that she shares with readers, giving hope to the world that history won’t repeat itself.

- Posted by Donna