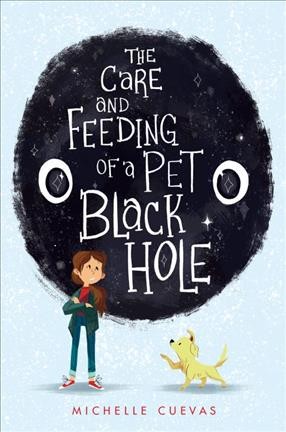

More than an adventure story, The Care and Feeding of a Pet Black Hole by Michelle Cuevas is an earth (space) science lesson as well as a grief healing journey. Overwhelmed by the pain of loss, eleven-year-old Stella Rodriguez narrates her story to her deceased father, whose “missing you feeling” follows her everywhere. With the Voyager 2 launch date only months away, Stella is desperate to visit with Carl Sagan who might send something into space for her on his Golden Record. On her way home from  the failed attempt, she encounters big needy eyes, “eyes that shimmered and seemed to have tiny galaxies inside of them” (9). The eyes, it turns out, belong to a black hole, a fact which Stella confirms after consulting her theoretical astronomy book.

the failed attempt, she encounters big needy eyes, “eyes that shimmered and seemed to have tiny galaxies inside of them” (9). The eyes, it turns out, belong to a black hole, a fact which Stella confirms after consulting her theoretical astronomy book.

Stella names her pet black hole, Larry, short for Singularity, the place of infinite gravity at the heart of a black hole. Because her life seems defined by gloom and bad dreams, Stella wants to put all of her memories into the nothingness that a black hole represents. Hoping to feel happy or even free, Stella feeds all of her problems to Larry. However, as she tries to get rid of everything bad in her life, Stella realizes that we often need those painful memories we try to dispose of because infinite love often accompanies infinite grief. Similarly, she learns to cherish her space cadet little brother, Cosmo, when she accepts that each one of us has annoying quirks and that “a person can’t just be the good parts. . . . Without the annoying parts, something vital is lost” (80).

In the same way that Sarah Lean’s protagonist Cally, in A Dog Called Homeless, befriends an Irish wolfhound, Stella’s pet black hole performs grief therapy—supplying hope, communicating affection, and listening to her woes. When Stella and Cosmo finally talk about their deceased father to remember him and to make his presence felt, the darkness in the black hole begins to dissipate and the pain performs its duty: cracking them open and letting in the light, reminding them that memories don’t have to morph into something bad and scary; that they can be “a safe place to go when [a person feels] sad or scared, lonely or lost” (171). Stella eventually embraces the truth that her home is not in the depths of the blackest black hole and relates home to something more like a locket—something you keep close and share if you want, a comfortable place where both memories and love live.

As she tells Stella’s story, Cuevas creatively employs allusions in her book, enriching it with space science details. From the characters’ names to the references to NASA, planets, stars, and constellations, all-things-astronomy play a major role in the story. My favorite is how from the great beyond, Stella’s dad tells her that she can talk to him anytime, that he lives in her black hole, not physically but “like the stars in our constellations. . . . Even if one star dies far, far away, its light is still visible, and the constellation it helped to make remains. A thing can be gone and still be your guide” (181). That metaphor has potential to heal other children grieving the death of a loved one.

- Posted by Donna