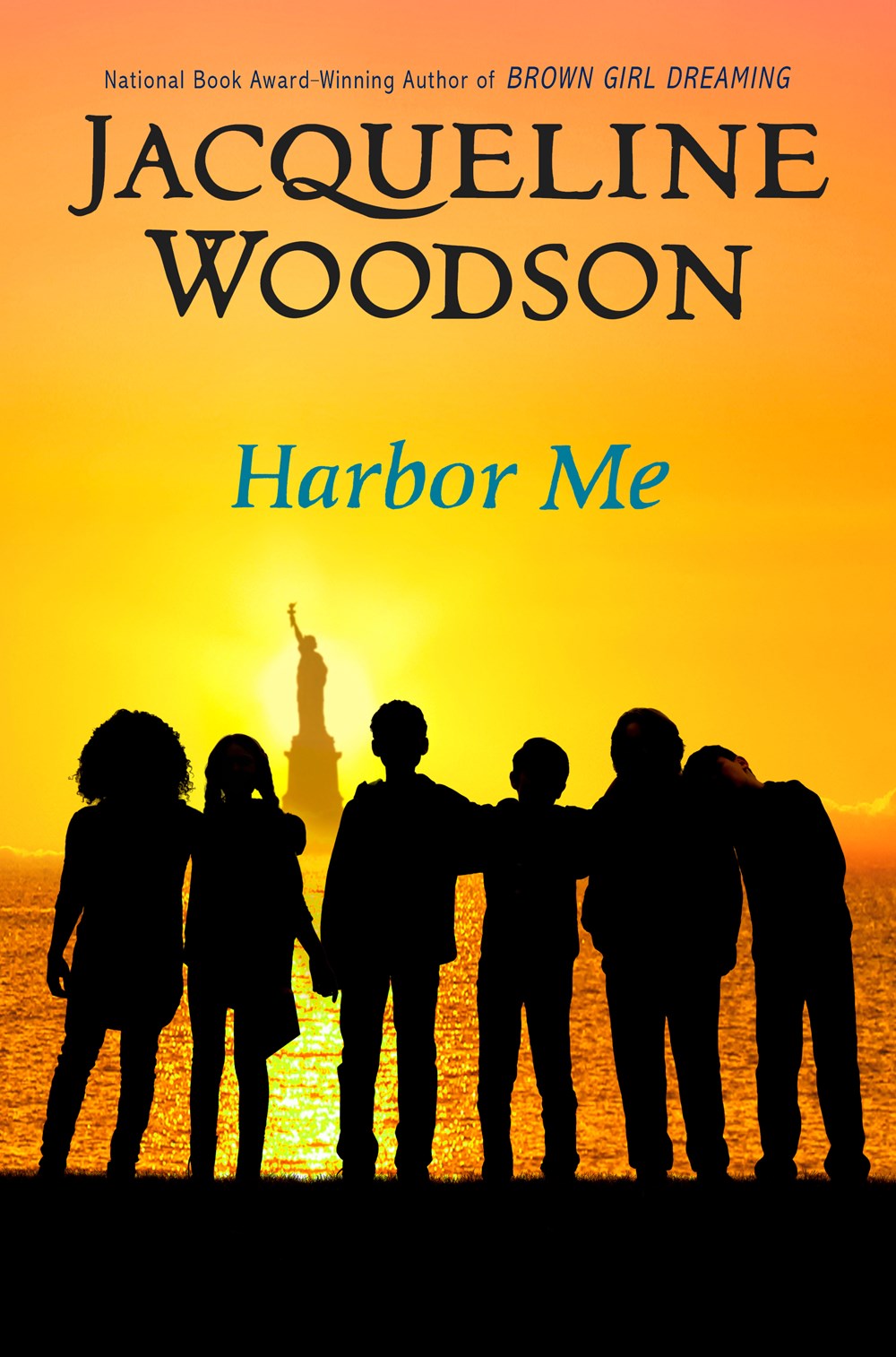

Jacqueline Woodson’s recent middle-grade novel, Harbor Me imparts how story holds the power to heal because it helps us make sense of the world. Woodson tells a tale about rising from tragedy and how tragedy not only takes away but bestows gifts.

Similar to other novels that use trees as metaphors for survival and interconnected relationships—novels like Hidden Roots by Joseph Bruchac, Wishtree by Katherine Applegate, and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith—Woodson’s book alludes to Ailanthus trees with their extensive root systems that help not only to ground them but to lend endurance in harsh conditions.

Set in Brooklyn, the native land of the Lenape Indians, Harbor Me features six special young people who are thrust together because they learn differently: Esteban, Tiago, Holly, Amari, Ashton, and Holly. These diverse youth are the students of Ms. Laverne, who knows the value of change and who honors confusion as a rich occasion for learning. Because we often see but don’t see that which is familiar, change ensures that we will confront the unfamiliar and that we will encounter the confusion that provokes inquiry.

To prepare her fifth and sixth grade students for the uncertainly that they will surely encounter in life, Ms. Laverne walks them down the hall one day to Room 501 and tells them this alternate space will be a place to talk, unattended by adults. Ms. Laverne realizes that the unfamiliar should not be frightening or avoided. She wants her students to develop their problem-solving skills, growth that will occur under the influence of disequilibrium.

In this room—which the group names the ARTT room (a room to talk)—the young people confront some of society’s biggest issues: racial profiling, deportation, English-only proclamations, incarceration, economic disparity, and manifestations of grief. Some of their deepest insights derive from these moments of confusion. These special learners come to realize that intelligence is not a matter of being smart but the capacity to view difficulty as an opportunity to pause, reassess, and employ strategies for making sense of problems.

Talking into a recording device, they tell stories that enable them to work through their fears and curiosities. In these stories, they discover commonality—despite their differences in racial, ethnic, and socio-economic status. They not only live out the effects of harmonic convergence but learn that a story can have many endings and beginnings.

Perhaps Holly, who is haunted by memories of her father’s arrest and her mother’s death, assesses the effects of her class’s learning the best: “I didn’t know the Unfamiliar would be beautiful and fun and heartbreaking and hard. . . . That it would be poems and pictures and questions. And answers” (175).

- Posted by Donna