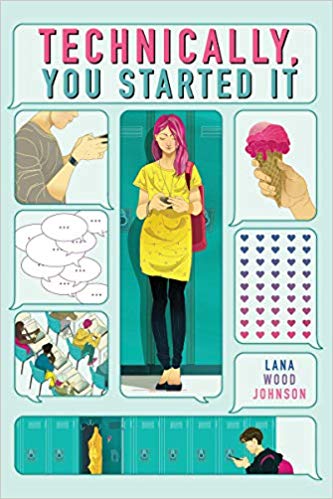

Lana Wood Johnson has written her new novel, Technically, You Started It, entirely in text message exchanges between two high school juniors: Haley Hancock and Martin Munroe II. Because the two teens share many things in common, they bond during these communications, realizing that they’d rather have their texting relationship “than nothing at all” (298).

Lana Wood Johnson has written her new novel, Technically, You Started It, entirely in text message exchanges between two high school juniors: Haley Hancock and Martin Munroe II. Because the two teens share many things in common, they bond during these communications, realizing that they’d rather have their texting relationship “than nothing at all” (298).

Martin, who is handsome, rich, famous, charming, and clever, is named after his financial genius grandfather who has funded most of the advances in science and technology. His father is not only a big risk-taker but someone who can’t “wait more than a second before getting remarried” (74), so he has been divorced two and a half times.

Haley, on the other hand, thinks things to death and has an overactive responsibility complex. Having been raised a nerd, Haley gets her propensity for technology, genealogy, and a general indifference to visuals from her mom. Although she isn’t religious, she believes in algorithms and spends a lot of time either reading or inside her head, two situations which contribute to her being somewhat socially challenged. Her parents are “a lone normal spot in a family of super weird” (74), and Haley’s mother’s super power is hearing phones on vibrate.

The two young adults are intelligent, well-read, and enrolled in Advanced Placement courses; however, they have complicated families. Martin’s family is Forbes and People magazine complicated, while Haley’s is Dr. Phil complicated. With them, texting becomes both habit forming and awesome since they are able to really talk to each other. Texting allows them the distance of the screen and the freedom to be their true selves. Eventually, they develop a friendship, talking genuinely to one another: “When I talk to you, I actually talk to you. It’s not just filling time. You know who I am” (213). They not only share their social anxieties and relationship insecurities but also aspects of themselves that reveal their philosophical cores. They discuss meaty issues like the competitive nature of school and how the gifted and talent program might just as well be called “Hunger Grades.” Yet their relationship turns out to be built on misunderstanding.

Readers of Johnson’s novel will likely share many of the same experiences and questions explored by the novel’s protagonists, questions like, why aren’t things easy when you like someone, or why does real life have to be so strange and weird-filled? They also discover that while anger goes away, disappointment lingers; it “fills the whole house [and] steals all the air” (191). Although during their discussions, the two teens generalize about girls being complicated and about guys hiding their feelings or playing Xbox to ignore their feelings, their conversations do reveal several human truths: that some friendships run their course while others can grow from a soul-mate spark, a chemistry that is based on “the person inside the skin more than the skin itself” (220). With references to the Kinsey Scale, we also recognize that people do not fit into exclusive heterosexual or homosexual categories.

- Posted by Donna