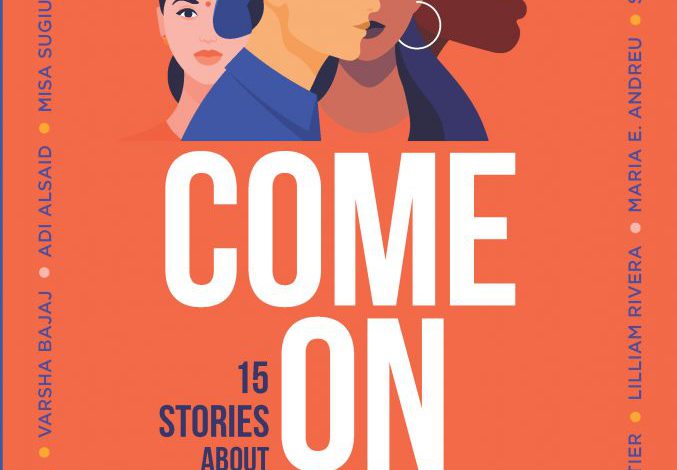

Edited by Adi Alsaid, Come On In is a collection of fifteen short stories that prove the immigration story is not a single story but one as varied as those who cross borders seeking survival or searching for a better life. The anthologized stories will spark some interesting discussion about the challenges posed for immigrants who lose a part of themselves when they choose life—a miracle made possible by migration.

Edited by Adi Alsaid, Come On In is a collection of fifteen short stories that prove the immigration story is not a single story but one as varied as those who cross borders seeking survival or searching for a better life. The anthologized stories will spark some interesting discussion about the challenges posed for immigrants who lose a part of themselves when they choose life—a miracle made possible by migration.

The stories also ask important questions about how to be both an immigrant and an American. Clearly, those who emigrate are not from families of “sitters or stay-putters” (246) but from pioneers of risk-takers—those who know the immensity and brutality of goodbye and those who know the depth of loss but also the offering of opportunity.

Some of the conflicts experienced by immigrants belong to that group alone—those who struggle between who they wish to be and who they are perceived to be: “Everyone preferred this fake version of me. Actual me wasn’t enough. . . . I wasn’t Persian enough (on Dad’s side), I wasn’t Turkish enough (on Mom’s side), I wasn’t feminine enough, I wasn’t straight enough, I wasn’t gay enough, and these days, I got the impression that my government was telling me I wasn’t American enough. I was born and raised in the States, but I still got asked where I was from. I know people didn’t mean Massachusetts” (32-33).

On this subject, one of the smartest responses comes from a character in Sara Farizan’s story “The Wedding,” when the protagonist’s grandfather says, “Don’t let anyone’s ignorance make you feel that you don’t belong somewhere. You belong wherever you are” (44).

The stories also broach the topic of ally behavior and how sometimes our fear of doing the right thing, the kind thing is greater than our compassion. That is a human response rather than one that belongs to immigrants alone. Another shared challenge is the question of identity—that difficult point of divergence when we worry that we are betraying our family (or our country) when we have “the outlandish dream of testing [our] boundaries and seeing how far [we can] go” (188), when we have to be stronger than our doubts and unfurl our wings, when we adopt new beliefs and ways of being in the world rather than accepting the limitations and parochialisms imposed by our families.

Along with the characters in the various stories, the reader will wonder what it means to be an American and whether we can be two things at once. We also wonder at the situation of being torn, and whether the pieces can be stitched back together, especially when the questions are so big and when “communication [may not be] one of the languages [our] family speaks” (293).

- Posted by Donna