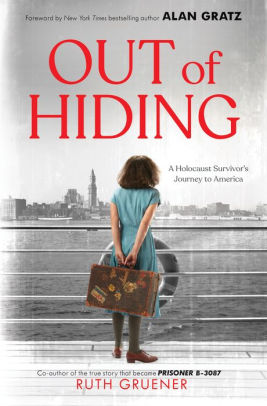

With her recent autobiographical account in Out of Hiding: A Holocaust’s Survivor’s Journey to America, Ruth Gruener (aka Luncia Gamzer) tells her story of survival. Her memoir joins those stories told by other survivors of this unimaginable time in history.

With her recent autobiographical account in Out of Hiding: A Holocaust’s Survivor’s Journey to America, Ruth Gruener (aka Luncia Gamzer) tells her story of survival. Her memoir joins those stories told by other survivors of this unimaginable time in history.

This was a time when anxiety turned to cold, raw fear as the Nazis burned synagogues and committed murder without regard for the sanctity of human life—a time when choice was taken, freedom was scarce, and normal took on an entirely different definition.

Gruener tells of her feeling like a nonperson, “a body that took up space” (27). She describes hunger, loneliness, hiding, and a life in shambles. Still amidst those dark and agonizing times, she found joy in a Chihuahua named Lala and hope in acts of compassion, such as the time her father stayed with a wounded German soldier until the ambulance came. From that act of bravery, Luncia learned the importance of not hating an entire group of people. “Everyone is an individual and deserving of dignity, and while there is evil in the world, there is always goodness too” (47-48). Because of the kindness, generosity, and bravery of non-Jews, many Jews survived the Holocaust.

However, whenever life began to go well for Luncia, something would happen to negate that ease—issues with paperwork, quotas for displaced peoples allowed to emigrate, and governments changing their rules—confusions and chaos that meant more time in limbo for Luncia and her family. Soon, she was unable to trust something good for fear it would be taken away. “If it weren’t for Hitler, I would have attended middle school, I would have had girlfriends, and I would have played the piano for nine years” (93).

“Fun” was a concept Luncia didn’t understand: “In Europe, life had been so much about survival. The idea of ‘fun’ seemed trivial, and a little childish” (149). Still, she realizes that no American teen will “want to be friends with a morose girl who can’t talk about the Winter Dance because she is having flashbacks of herself with frostbite and of a baby getting thrown out a window by a Nazi” (157).

In her cynical moments, Luncia wishes for amnesia so that her memoires will be wiped out without a trace. Tired of fighting and drowning in the storm raging inside her, Luncia tries forgetting and moving on. Gradually, she realizes that holding on to the feelings of a scared girl in hiding involves copious amounts of mental energy that detracts from her ability to enjoy the new life she is building. While forgetting is not an option, there is a difference between remembering something tragic that happened and talking about that memory, and constantly reliving it. When she began making peace with the past, she realized the power the flashbacks had over her slowly dissipated.

This is an important book because it invites readers to embrace the notions of tolerance and peace, especially at this time when so much prejudice, hate, and racism still exists in the world. Gruener tells readers that there is beauty in variety and difference. “We share the same humanity, and we are deserving of empathy. . . . There is more that unities us than divides us (185).

- Posted by Donna