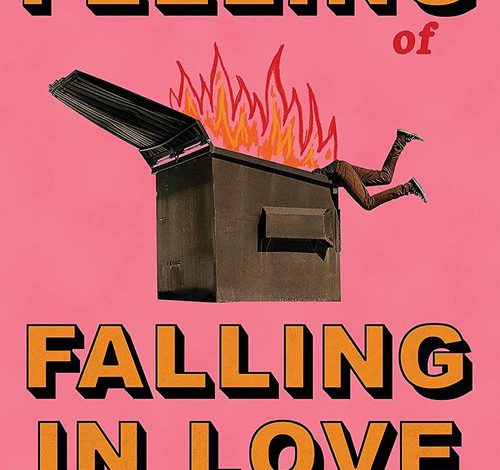

Although Mason Deaver’s novel The Feeling of Falling in Love is indeed a love story, as the title implies, it is also about self-esteem, social class differences, and the exploration of sexual and gender identity.

Neil Kearney, a transgender teen, has a “friends with benefits” relationship with his friend Josh. Both use the relationship for stress relief and mutual pleasure. However, when Josh decides he loves Neil, Neil panics and invokes the Pull-Out Clause. Now, he has a week to prove to Josh that he has moved on with his roommate, Wyatt Fowler. What could possibly go wrong, especially since Wyatt claims to be a good actor?

Eventually, readers learn that Wyatt may be a pansexual teen. Aspiring to be a musician, he has a smooth voice and fingers that move effortlessly on the strings of his guitar, which is a natural extension of his body. Neil promises to pay Wyatt for his time as the pair conducts their ruse, one that involves their attending a wedding in California. Neil’s brother, Michael, is getting married, and Neil is a groomsman in the wedding party.

Wondering what it feels like to be comfortable around family, Neil has survived multiple variations of trauma from divorce, parental neglect that made him feel second best, and transphobic microaggressions from grandparents who think Neil’s just going through a phase and who declare if he’s “going to be a boy, [he] should at least stand like one” (208). As a defense mechanism and to protect himself from disappointment, Neil never has any expectations from his family, whom he calls “awful, terrible people” who simply throw money at a problem to solve it.

Two actors in a play, Wyatt provides support to Neil through all this abuse, and gradually the ruse brushes up against reality. With Wyatt, Neil gets more than a glimpse into the class divide and realizes his privilege has colored his perspective and impacts his behavior.

Under the influence of Deaver’s pen, the reader also gets a story about teen anxiety and insecurity. Afraid that he will get hurt, Neil practices self-sabotage and pushes away people who love him, saying: “I don’t deserve anything but loneliness because all I do is hurt people” (264). In our anxiety, we tell ourselves lies and invent falsehoods about rejection, hatred, and alienation that undermine our self-worth. From Deaver’s characters, readers come to learn the harm in granting fear the power to paralyze us from exploring possibility and when we allow our parents’ relationship to negatively sway our thinking and behavior.

At one poignant moment in the text, Josh defines love: “I see it more as knowing what the other person needs and doing whatever it takes to find it, because somehow your own happiness has become inseparable from theirs. Because it makes you so damn happy to see them happy. And it makes them happy to see you happy” (283).

In another key scene, Neil’s mother tells him: “When you’re [a teenager], everything feels like the end of the world. Everything feels so big, like it’s going to impact you for the rest of your life. But that’s just part of life, part of relationships. . . . Being scared of messing up just shows that you care. . . . But you also need to let yourself have your feelings, to stop being afraid of going after what you want, of going out and getting it” (297). Neil had earlier observed that “it’s kind of sick that we’re expected to know what we want to do with the next sixty years when we’re sixteen” (146).

- Posted by Donna