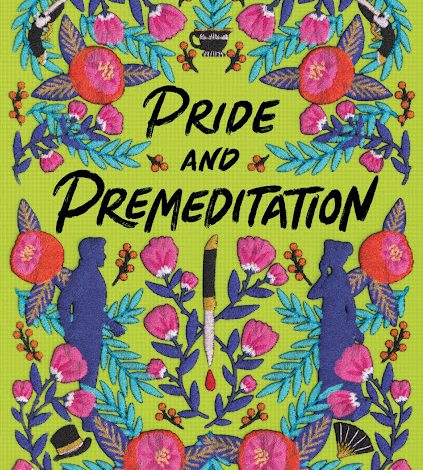

Written in a fashion similar to that of a fractured fairy tale, Pride and Premeditation is a tongue-in-cheek retelling of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Although Tirzah Price employs many of the same characters and even opens with a play on Austen’s original line, “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a brilliant idea, conceived and executed by a clever young woman, must be claimed by a man” (1), she takes other liberties.

While Price makes an effort to stay true to the etiquette and customs of the early nineteenth century, Lizzie Bennet’s ambitions to become a barrister—or even a solicitor—would have been out of reach in 1813. Still, the romance elements are present, along with a murder mystery. Price prizes satirical intent and playfully mocks the mores of the time through her character’s action.

Some of the prime moments in the novel are those when seventeen-year-old Lizzie rises with courage just as someone else attempts to intimidate her. With an inclination for order, Lizzie is passionate about knowledge, hard work, quick thinking, and the pursuit of justice. The cases that unfold in her father’s office are far more fascinating than any drama that might occur in the drawing room. After Mr. Collins steals her ideas and passes them off as his own, Lizzie is determined to solve a murder to prove to her father that she is worthy of a real job at Longbourn & Sons. She must not only use logic and common sense but be more capable than any man as she attempts to prove that Charles Bingley did not murder George Hurst, his sister’s scoundrel of a husband.

In the process of her sleuthing, Lizzie crosses paths with several interesting characters: Caroline Bingley, George Wickham, Fitzwilliam Darcy, and Lady Catherine to name a few. Suspects abound, along with pirates and pretense.

Tucked into the plot, Price explores some of the social injustices of the time, namely that someone with a darker shade of skin is considered “unworthy of respect” or assumed a thief.

Lady Catherine also alludes to the social gathering and balls of the time as “a beautiful façade for what [they] truly represent. . . , a marriage market. All the young ladies want good secure matches and a step up the social ladder. All the young men want a pretty wife to add to their fortunes. Their parents scheme along the sidelines” (131).

Another sentiment shared by the author is that about the human tendency to judge by reputation rather than by fact and experience. Regardless, still today, a reputation in doubt or tarnished is nearly impossible to restore. “People will gossip. . . . A good opinion, once lost, is lost forever” (161). Other readers might side with Darcy, who says: “I’m not responsible for what society may think. If anyone is foolish enough to let rumors or unproven suspicions color their opinion of someone, they are not worthy of my respect” (161).

To that remark, Lizzie replies: “That’s an essay opinion to hold when you already have a position and a fortune” (161). At other moments in the text, Lizzie points out additional social injustices; for example, that a woman often pays dearly for a man’s misdeeds.

Although occasionally prone to misunderstanding, both Darcy and Lizzie are strong-willed, sharp-witted, determined, and loyal to the point of sacrificing their own reputations—even their own lives—for the people they love.

From this pair, the reader will learn much—not only about grit and the sense of justice but about humility. As they open up about their vulnerabilities, they also eventually give credit where credit is due—expressing gratitude to all of those who play a part in helping to unravel the novel’s mysteries. Yet, those solutions come with a cost.

Price has creatively entwined the sly and witty social commentary of Jane Austen with the twisting mystery of Agatha Christie to write about an ambitious young woman who refuses to be controlled by the limitations of her era or stifled by drawing room etiquette.

- Posted by Donna