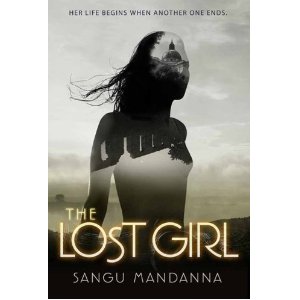

Readers who followed the paranormal romances in Stephanie Meyers’ Twilight series, Maggie Stiefvater’s Shiver trilogy, or Alisa Valdes’ The Temptation will likely find Sangu Mandanna’s debut novel, The Lost Girl, thrilling. Besides the interesting love triangle to fuel the plot, however, Mandanna adds adventure, mystery, and a twist on New Zealand folklore. With a science fiction “what if” style, the novel also poses some provocative questions about creating life through processes that parallel cell regeneration or even cloning. Given these features, the book transcends the typical romance novel to become deeply philosophical.

Readers who followed the paranormal romances in Stephanie Meyers’ Twilight series, Maggie Stiefvater’s Shiver trilogy, or Alisa Valdes’ The Temptation will likely find Sangu Mandanna’s debut novel, The Lost Girl, thrilling. Besides the interesting love triangle to fuel the plot, however, Mandanna adds adventure, mystery, and a twist on New Zealand folklore. With a science fiction “what if” style, the novel also poses some provocative questions about creating life through processes that parallel cell regeneration or even cloning. Given these features, the book transcends the typical romance novel to become deeply philosophical.

Despite her name, which means immortal one, Amarra knows life’s limitations. Created without love by Weavers, Echoes emerge from the Loom and grow early into the knowledge that they are owned. Ordinary people, who cannot bear the idea of losing somebody they love, can pay the Weavers to make an echo. These echoes of another life live as understudies of the lives they may someday replace. Some see these copies as “angels among mortals” (38) because they step in when someone else dies and because they sacrifice everything to give another family hope and happiness. Others see them as abominations without feelings and thoughts, nothing more than Frankenstein-like monsters. Perhaps they’re both, at once glorious and dangerous.

Marked on the neck with the Weaver’s crest and bound by the laws and the rules of the Loom, an echo has little freedom and lives in constant fear of trackers, seekers, hunters, and being “unmade” by a potential Sleep Order.

At sixteen, Amarra, who is neither the steady and cautious nor the obedient type and whose familiars live inIndia, longs for her own human life. Following an illegal trip to a zoo in the English countryside to see the elephants, she names herself Eva after a similarly independent creature. At the zoo, Sean tells Eva, “Being different doesn’t make you less than the rest of us” (38). After tasting independence and establishing her identity, Eva wants to wear all her differences without shame.

Profound moments like these are prevalent in the novel, which stimulates critical thought. As a bold, tough text, the book poses the following pondering points:

- Based on your own social experiences/interactions, comment on the accuracy of Sean’s assertion: “Being different doesn’t make you less than the rest of us” (38). In what real-world examples do you see that truth not followed?

- According to events in the book, love often motivates us to behave in puzzling ways: fulfill requests we consider detestable, seek to replace an unbearable loss with a copy, risk our lives, wish for life beyond death (40). What real-world examples can you offer of love’s puzzling power?

- Why do we struggle to wear our differences without shame? To what degree have you won or lost that struggle?

- On page 42, Eva and Sean discuss the difficulty of letting go of a loved one at death. Does anyone ever really let go of the people they love? Is it right to try? Why/why not? Is it right to try to replace the loss? Why/why not?

- The author picks up this thematic thread again on page 159 and invites readers to consider how humans struggle to erase the pain of loss. What power do the dead have over the ones they leave behind? Mandanna describes “this deathless love that human beings continue to feel for the one’s they’ve lost” as “strange and beautiful and frightening” (159). Later, on page 263, she describes dead loved ones that linger as “benign and sweet and painful.” How would you describe a deathless love and loved ones that “echo all by themselves”?

- To what extend does love have power to create happy endings? In the absence of love, teaching, care, and nurturing, Eva suggests rejection can lead to an anger and a sadness that engender horrible acts. To what extent do you agree or disagree?

- What equivalent does contemporary society have of the hunters, vigilantes, or secret societies “set on stopping the creation and survival of unnatural things” (48)?

- Consider the tale of the mongoose told on page 54. To what degree is it human tendency when disaster strikes to turn first on the creatures we have nourished, cared for, or loved?

- Based on real-life events, comment on Matthew’s assessment that one “can’t be powerful without being ruthless” (114).

- In the discussion about Frankenstein, Mrs. Singh wonders how anyone could love something that was made unnaturally. What do you think of the teacher’s logic? If a baby is conceived unnaturally (i.e. in a test tube) would its parents be incapable of loving the child?

- Neither Eva nor Lekha believe that committing some horrible act automatically makes a person evil (207-208). What about you?

- Lekha suggests that expecting the worst of someone denies the individual a chance to be better; what do you think?

- What evidence can you provide from the natural world or from contemporary society that “the shiniest, prettiest things can be the most dangerous” (266)?

Young adult books like Mandanna’s offer rich opportunities for wrestling with difficult topics and for examining life from all its black and white and shadowy angles. Eva’s story contains warped threads of slavery, oppression, marginalization, and hatred. In the weft are desires for freedom, survival, acceptance, and love. With her creative tapestry, Mandanna seems to suggest that life is a constant struggle to win our independence and to keep ourselves from coming unstitched. We want our lives to be our own and in our struggle we often waste our lives by being careless. In this battle, relationships and love are the rewards—but in a cruel paradox, they’re also the penalties.

- Posted by Donna