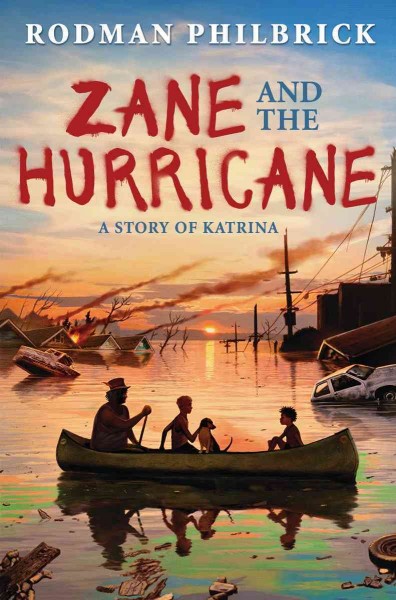

Newbery author Rodman Philbrick‘s latest, Zane and the Hurricane: A Story of Katrina, is what prompted these musings. August 2005 isn’t all that long ago, but like the most people, I admit to being marginally aware of the crisis that engulfed New Orleans and the rest of the cities, towns, and people who were impacted by Katrina. News outlets did their best (and maybe their worst) to keep us informed of what was happening; but the individual human truths, the victims’ plights, the heroes’ courage, and the scope of the devastation, didn’t really get through to me like I believe it should have. What’s more, I had no idea the extent to which the undercurrents of hatred, racism, poverty, and social injustice that had long simmered in New Orleans were allowed to break loose from their “levees” and go unchecked amongst the chaos of those terrible days in August 2005.

Philbrick’s novel, intended for grades 5-9, is told with the clear-eyed, thoughtful perspective of a boy visiting New Orleans for the first time to meet his here-to-fore unknown grandmother. Zane has both the perspective of an outsider and a child, who can honestly see, and authentically react to, the scope of a situation without the rationalizations, justifications, and self-delusions of an adult. Thought-provoking, age-appropriate, and thoroughly engrossing, Zane and the Hurricane is a much needed exploration of devastation, injustice, and the power of human courage, hope, and perseverance.

- Posted by Cori