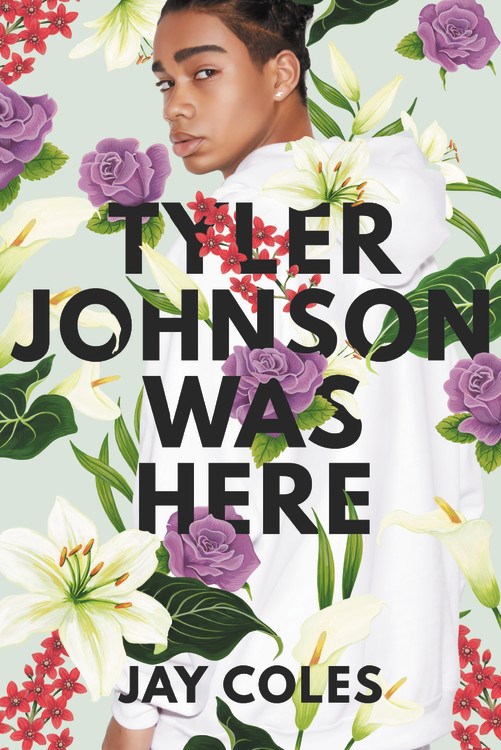

With his debut novel, Tyler Johnson Was Here, Jay Coles tells the story of Tyler and Marvin Johnson, twin teenage boys living in Sterling Point, Alabama. In their neighborhood, they worry often about police visits, gang-infested streets, robberies, vandalism, and gun violence. For eight years, their father has been in Montgomery Correctional Facility for a crime he did not commit, and Marvin would “kill to have him back” (19). Because he hung around men who committed crimes, Jamal Johnson received his sentence from a corrupt system. To cope with his dad’s absence and to see past the shame, Marvin writes letters to his absent father, who shares his wisdom from behind bars: “You do deserve to have your voice heard” (186).

With his debut novel, Tyler Johnson Was Here, Jay Coles tells the story of Tyler and Marvin Johnson, twin teenage boys living in Sterling Point, Alabama. In their neighborhood, they worry often about police visits, gang-infested streets, robberies, vandalism, and gun violence. For eight years, their father has been in Montgomery Correctional Facility for a crime he did not commit, and Marvin would “kill to have him back” (19). Because he hung around men who committed crimes, Jamal Johnson received his sentence from a corrupt system. To cope with his dad’s absence and to see past the shame, Marvin writes letters to his absent father, who shares his wisdom from behind bars: “You do deserve to have your voice heard” (186).

The boys, who attend Sojourner Truth High School, a predominantly Black/Hispanic high school with the highest number of physical altercations, have grown up with THE talk. Delivered at least once a month by “all decent black mothers and fathers” (25), THE talk cautions black children about being careful and staying out of the streets because they live in a white-man’s world.

Because Marvin and his friends, G-mo and Ivy, are college-bound, focused on their goals, and motivated to escape the typical stereotypes, in the hood, they are called Oatmeal Cream Pies—”brown on the outside, white in the middle” (30). They are known as “high ability geeks” because they love science and watch the television show A Different World as if it were a religion. From the show’s relatable cast, Marvin learns what it means to be black, successful, and daring. He refuses to fulfill the prophecy the world has predicted for him.

However, Tyler, a talented musician and basketball player, seems more troubled and unsure about his future. When he starts hanging out with Johntae and dudes like him who smoke weed and sell drugs, Marvin begins to worry; he doesn’t want his brother to be plucked from his life like his dad was, so he calls “bullshit” on his brother’s excuse for gangster behavior: “Look, Marvin, it’s not easy without Dad around, and Mama can’t support us on her own. You see her struggling. Can’t pay the bills, let alone send you to college. Johntae’s going to help with that. So that’s all this is” (52).

Stuck in the gray area between grieving the absence of his dad and watching his brother slowly vanish before his eyes, Marvin attends Johntae’s party out of love and protection for his brother’s well-being. After gun shots ring out and police raid the party, Johntae is arrested and Tyler disappears. In the search for his missing brother, Marvin learns lessons about police brutality and oppression, the preferential treatment that defines racism, what it means to be a concerned citizen, and what it means to be black and looked at as a threat before actually being seen.

Although his Auntie Nicola used to be a cop, and a good one, Marvin begins to feel suspicious about police officers, wondering, who do you call when the cops are the ones being the bad guys? Thinking he’ll die from brokenness and rage, Marvin seeks out help where ever he can find it, including from Faith, Johntae’s former girlfriend. To Marvin, Faith is more than flesh and bone and beauty; she’s “hella bomb.”

Eventually, the police find Tyler, who is just going home, he says. But when Tyler pushes the cop away, Thomas Meredith shoots him three times. The brother Marvin tried so hard to save has become a statistic. Drowning in a shallow pool of hatred, Marvin wonders how he will go on, now that his brother is dead. When he is in an especially dark place, empty of feeling and hope, Faith reminds Marvin that he matters, “because sometimes being alive just isn’t enough” (152). Faith, who lost her best friend Kayla in a drive-by shooting, can relate to Marvin’s deep sense of loss: “I know that ache inside your heart. And I’m living proof that losing a loved one doesn’t stop you from beating yourself, blaming yourself, wanting to die yourself, but Kayla is in me as much as Tyler is in you. They’d want us to fight, not surrender” (198).

Taking inspiration not only from Faith but from Frederick Douglass, who prayed for twenty years but didn’t see anything happen until he got off his knees and started marching with his feet, Marvin vows to find justice for Tyler and to preserve his legacy. Wanting the world to know his brother was here, to know that Tyler mattered, to know that his brother was a bright and loving basketball prodigy, Marvin resolves to be the change he wants to see in the world. He channels his hurt into anger and his anger into productive action. With his friends, he decides on a place, decides on a time, and sends out messages over social media, inviting people to a protest. Marvin hopes to make people know that black skin isn’t dangerous, that hoodies and low-riding jeans don’t identify a thug, and that peace and equality shouldn’t be so hard to achieve. He wants justice for the Trayvon Martins and the Emmett Tills of the world. On his journey for justice, Marvin learns that life is about confronting a storm’s fury while holding on to hope and using anger to leverage the power needed to get people to pay attention, to listen, and to effect change.

In Tyler Johnson Was Here, Coles writes with a realism that makes the reader think he has experience with a grief that grabs at the throat, choking the oxygen right out. That he knows the agony that time causes: “Time does not heal. It only anesthetizes” (253). Coles also inspires readers to never give up or give in. From his resilient and determined characters, we realize that we, too, can find contentment if we focus on our goals, if we refuse to allow others to define us, and if we speak out about things that matter. As the authors of our own life stories, we shape our destinies by the choices that we make.

This novel is an important commentary on current race relations in our country. It invites critical thinking not only about the meaning of freedom but about the effects of silence. Coles confirms that silence is not an effective strategy in addressing oppression, that talking about racism in our society and how to interrupt it is important for everyone.

- Posted by Donna