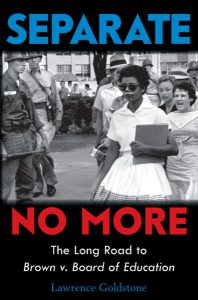

Perhaps the most widely recognized Supreme Court case in American history, Brown v. Board of Education was a nationwide assault on beliefs of white supremacy. But for all its renown, many Americans know little about the case itself or of the great changes in American society that propelled the Supreme Court to rule as it did on May 17, 1954. With his Scholastic published book Separate No More, Lawrence Goldstone enlightens readers about the long road to Brown v. Board of Education.

Perhaps the most widely recognized Supreme Court case in American history, Brown v. Board of Education was a nationwide assault on beliefs of white supremacy. But for all its renown, many Americans know little about the case itself or of the great changes in American society that propelled the Supreme Court to rule as it did on May 17, 1954. With his Scholastic published book Separate No More, Lawrence Goldstone enlightens readers about the long road to Brown v. Board of Education.

In this nonfiction account, readers will learn the names of many personalities instrumental in proving that separate did not mean, and could not be, equal. We also encounter the great disparity and egregious wrongs that prevailed during the Jim Crow era. On this journey, readers meet not only the typical personalities of Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Linda Brown, but unlikely, lesser known people like Irene Morgan, Charles Houston, and Esther Brown.

Even though the decision on Brown v. Board of Education was made fairly recently, it has been long enough ago that we should have learned from its history lessons. However, we still require reminders, and Goldstone’s research provides them.

One of my favorite lessons lies tucked into Washington’s words and should be read from the rooftops today: “Our greatest danger is that in the great leap from slavery to freedom we may overlook the fact that the masses of us are to live by the productions of our hands, and fail to keep in mind that we shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labor, and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life” (32).

Although in the early 1900s Du Bois attacked segregation, racism, lynching, and the widespread belief among whites that African Americans were racially inferior, some pockets of society still harbor elitist thinking. Just as surely as we require water, we need the reminders of the Niagara Movement, “the first national organization of Negroes which aggressively and unconditionally demanded the same civil rights for their people which other Americans enjoyed” (42) and of the conditions that gave birth to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, which denounces the “ever-growing oppression of . . . colored citizens as the greatest menace that threatens the country” (50).

Goldstone’s text includes excerpts from The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races. Created by Du Bois, this magazine is “arguably the most widely read and influential periodical about race and social injustice in U.S. history” (52).

Among those lesser known personalities, Charles Hamilton Houston cast a large shadow on the struggle for equal rights. He was “a combination of high intellect, dedication to social justice, commitment to hard work, and precise application of the law” (111) that would be required to win big cases against white adversaries.

As it is wont to do, history has come to bear on the present. Just as Chief Justice Earl Warren deeply regretted his mistreatment of the Japanese following the attack on Pearl Harbor by later fighting for “the American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens” (212), we continue to set right the wrongs society has committed.

One of those efforts occurred on January 20, 2020, Martin Luther King Day, when Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly announced that a new aircraft carrier would be named the USS Doris Miller. This is the first aircraft carrier to be named for an African American and also the first for an enlisted man. Dorie Miller had earlier in his military career been awarded the Navy Cross, the first ever given to an African American.

But we still have work to do. Although Brown v. Board of Education “states without qualification that separating people, diminishing people, enslaving people simply because of the color of their skin” (244) is wrong, we need to embrace differences beyond just race. Goldstone’s book can inspire readers to make progress towards social justice in all of its forms despite the challenge such work entails. In the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.”

- Posted by Donna