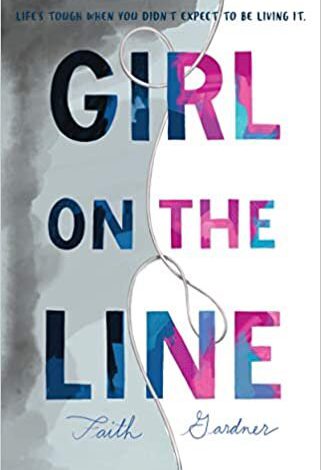

A form of cognitive efficiency, labeling helps people make sense of their worlds. Although labels give our brains the ability to categorize and to draw useful conclusions, they can also limit thinking and lead to stereotypes. With labels like normal, mentally ill, or bipolar, we not only make assumptions about others but about ourselves and our potential abilities. These assumptions can even influence our identities. It is this identity labeling that concerns Journey Smith, the seventeen-year-old protagonist in Faith Gardner’s novel Girl on the Line.

A form of cognitive efficiency, labeling helps people make sense of their worlds. Although labels give our brains the ability to categorize and to draw useful conclusions, they can also limit thinking and lead to stereotypes. With labels like normal, mentally ill, or bipolar, we not only make assumptions about others but about ourselves and our potential abilities. These assumptions can even influence our identities. It is this identity labeling that concerns Journey Smith, the seventeen-year-old protagonist in Faith Gardner’s novel Girl on the Line.

Journey doubts the truth about many of the things the world tells her and believes that her brain ruins everything as it strives for efficiency. Journey has always had “big feelings,” with a tendency towards being dramatic and volatile. “Sometimes these big feeling make everything wonderful and Technicolor, and sometimes they make everything a parade of horrors” (314). Perhaps her best friend Marisol Cruz captures the essence of Journey’s personality when she says, “You are so . . .much. . . . It’s why I love you. Why everyone does. You’re such a damn flame, we all want to be around you” (68).

However, after her parents’ divorce and a near death experience in a car accident, Journey feels unable to face life at all. After her suicide attempt, her boyfriend Jonah Patterson decides he needs space. This series of traumas sends Journey into a state of such confusion that she is unsure which side of the crazy person fence she lands on. Does she need therapy, drugs, or a diagnosis to live a full and happy life?

To make life easier for herself and others, she wishes she could just land on that proper word that fits her. Whether she is teenager going through a tough time or one who is experiencing post-traumatic stress related to her life situations or one with a depressive disorder, all Journey wants is to be happy and whole. Feeling as though she is always a mere millimeter from madness, she forces herself to keep going.

Although Girl on the Line tells Journey’s story, it could be the story of almost any neuro-atypical teen. And Gardner’s book reads like a self-help manual for such teens. It reminds us all that the decisions we make are not ours alone; they affect those around us. Just as Journey’s suicide attempt isn’t only her story to tell, it impacts the lives of her family and friends. “I hate that my suicide attempt happened. I hate how it hurt, but I hate most how much it hurt everyone around me” (218).

While Journey struggles to find her way again, she accepts a position as a crisis line volunteer. Hoping that she can help someone else who is where she once was, Journey learns the value of being there as well as the limitations on being able to fix what ails another person. As she learns the difference between surviving and living and thriving, Journey realizes that many aspects of her racing mind are simply part of the human condition. She also comes to accept that humans are quick to put others into boxes or to believe that people might be “fixed with” prescriptions. In fact, sometimes young people don’t have anything wrong with them. Instead, parents might be impatient or schools expecting children to all learn with the same methods at the same pace. We might do better and medicate less if we were to improve public education and encourage different methods of teaching or adjust our expectations for children’s’ behavior and teach them better avenues of self-expression. And sometimes, brokenness is an improved form of wholeness.

Gardner’s book invites us all to rethink how we define normal and what we think of as mentally ill. Throughout our lives, people attach labels to us, and those labels reflect and affect how others think about our identities as well as how we think about ourselves. Although labels are not always negative—since they can reflect positive characteristics, set useful expectations, and provide meaningful goals in our lives—we must dispense them with caution and accept their limitations.

Journey may capture the sentiments of many of us when she says, “I want to know what I am, what to call myself, whether to call myself anything, what treatments there might be. I’ve doubted that I’m bipolar at times. Others, I’ve felt like it fits. I hate the fact that I have to label myself at all. But if I have to label myself, I want to get it right” (336).

- Posted by Donna