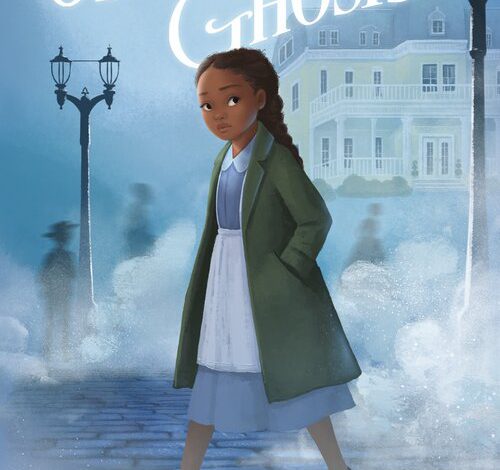

Justina Ireland explores the notion of unfairness in her novel for middle grade readers, Ophie’s Ghosts. Readers will accompany Ireland on this justice-seeking journey as she asks important questions: How do we live, survive, and thrive in a system that is unjust? How do we remain strong and unbent, willing to do the right thing, even when it puts our own comfort and lives at risk? What are we willing to put on the line in the name of justice that is denied to us? How do we grieve when the ghosts of our loss appear in the everyday suffering of those around us?

Justina Ireland explores the notion of unfairness in her novel for middle grade readers, Ophie’s Ghosts. Readers will accompany Ireland on this justice-seeking journey as she asks important questions: How do we live, survive, and thrive in a system that is unjust? How do we remain strong and unbent, willing to do the right thing, even when it puts our own comfort and lives at risk? What are we willing to put on the line in the name of justice that is denied to us? How do we grieve when the ghosts of our loss appear in the everyday suffering of those around us?

As our tour-guide, Ireland pens Ophelia Harrison into being. When she is twelve, Ophie sees her first ghost, and it was the last time she saw her father. After losing her father and her home to ugly acts of violence in Georgia in 1923 when Jim Crow laws ruled the South, Ophie and her mother flee north to live with family in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—“a city of steel and iron, coal and power” (20).

Because she can see and even speak with the dead, Ophie initially thinks her brain is sick, but her Aunt Rose explains how “back before white people bought Negroes and brought them to America, our ancestors were responsible for talking to the dead. The women in our family were respected and consulted whenever a loved one died” (74) to help them move on or to listen to their stories so that they could be told and remembered. “Most folks just want someone who will hear them, who will see them. The dead are no different” (74).

For Ophie, it is hard to imagine a time when colored women were sought out and respected for their abilities and not “treated like bothersome pests by white folks” (73) or expected to serve their needs. Ophie craves that kind of comfort.

Instead, she lives in a strange city with relatives who mostly aren’t very nice and works in a scary old house for the mean Mrs. Caruthers of Daffodil Manor. All Ophie really wants is to go to school and for her mama to be happy again. While others seem to have everything, Ophie and her mama are forced to work and accept charity. Fearing that the best parts of her mama were destroyed by acts of violence and that all of her good memories burned down with their house, Ophie is desperate to find solutions to the unfairness of their predicament.

Despite her Aunt Rose’s cautions about the danger of ghosts, Ophie befriends Clara at Daffodil Manor. When she discovers that Clara was murdered, Ophie makes it her purpose to help Clara solve the mystery of her death so that she can move on. As the story unravels, Ophie meets several ghosts, and even though the task seems impossible and overwhelming, Ophie decides it is her duty to help them.

By the story’s end, Ophie cries—releasing tears for girls who believe in happily ever afters but end up murdered in an attic, for boys who are whipped and beaten for protecting brothers, for men who want their voices heard but whose voices are choked off forever, and for all the dead who still wait for someone to help them.

With her numerous references to unfairness, Ireland invites readers to consider the human tendency to draw lines. “Line across class and lines across race, lines between the immigrants and those who had lived in [a place] more than a handful of years” (322).

Anne Roiphe makes a similar invitation in her book A Season for Healing: Reflections on the Holocaust. She encourages us “to look closely at the border where our empathy ends” since there is potential at these margins for intolerance to grow and cruelty to begin.

Lines. I suspect we all have them—those sometimes inconsistent, sometimes shifting, sometimes contradictory markers that we use to define “acceptable” under certain conditions at certain times for certain individuals. Assuming these lines exist, we must then wonder (and perhaps question) whose lines are privileged, challenged, ignored, or denied within the communities in which we live.

Because our actions have implications, knowing our borders and admitting that certain topics/issues cause pangs of intolerance might help us to address our biases. While we don’t have to let go of our beliefs, perhaps we can accept that other ways of knowing and believing exist and that our reality isn’t the only one. With that acceptance, our borders might begin to blur. As we struggle against certain assumptions, we may begin to unlearn certain truths and to make room for new learning. These are both Ireland’s and Ophie’s hopes.

- Posted by Donna