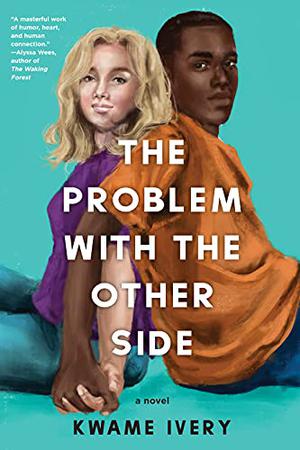

Anyone interested in reading a book that will prompt a deeper understanding of the complexities of racism should find a copy of The Problem with the Other Side by Kwame Ivery. This occasionally humorous but heartbreaking novel follows the lives of a pair of teens in New Jersey whose sisters decide to run for study body president.

Anyone interested in reading a book that will prompt a deeper understanding of the complexities of racism should find a copy of The Problem with the Other Side by Kwame Ivery. This occasionally humorous but heartbreaking novel follows the lives of a pair of teens in New Jersey whose sisters decide to run for study body president.

By alternating between the perspectives of Sallie Walls and Ulysses Gates (aka Uly), Ivery invites his readers to confront their own biases while also considering the nuances of a mixed-race relationship in a world where two people with a simple pigmentation difference often cannot date without repercussions.

While participating in high school theater, sophomores Sallie and Uly bond over their love for the film The Good, the Bad and the Ugly and discover an attraction for one another. Not a fan of classic and boring beauty, Uly appreciates “Quirky, curveball beauty. Beauty that makes [a person] wonder” (48). Although Sallie’s sister Leona is a head-turner, Sallie is a mind-turner with “the deep, hypnotic voice of an Amazon warrior” (48).

A romantic, Uly makes Sallie feel like a walking generator. She finds him funny, cute, nice, edgy, and stylish—all in the same package. However, Uly isn’t a fan of his romantic side because the engine of a romantic runs on the heart and just like an engine, it has the potential to break down.

As tensions escalate at Knight High School and Leona decides those are tied to racial unrest, she coins the phrase Turn Knight Back into Day and uses it as a platform for her presidential campaign. In response, Uly’s sister Regina alters all of Leona’s posters to read: Turn Knight Black Today and runs as her opponent. With their siblings serving as their campaign managers, the two presidential candidates throw shade at one another while Uly and Sallie attempt to keep their relationship separate but united. Despite their best efforts, the pair get caught in the middle of racial tension. When either one rewards a sister, each experiences a conflict of interest and a threat to togetherness. Both try to crack the code of cultural border crossing and to mediate the extremist positions they see in their sisters’ “hate-orade.”

The multiple conflicts encourage critical thinking on the part of the reader. At one point, Ivery has his character Leona say: “The kids who hung up those [Confederate] flags are no more wrong than those who vandalized them. Do you know what it’s like when something that means so much to you is vandalized? All because the vandalizers think they have a right to destroy something they disagree with. . . . Every object in this world is, like neutral. It’s us who make it into something more: we make it into something racist if we prefer to be the victim, or we make it into something hopeful if we prefer to be somebody who looks at the brighter side of life” (248).

As the school’s makeover ensues and each new takeover of popularity manifests, the reader wonders whether such nastiness needs to be part of the campaign process. Perhaps it does, as hidden agendas and ugly truths get unearthed. One also wonders how often money gets used to leverage votes. As one character remarks, “Insults fade when you get paid” (277).

Worth the read, Ivery illustrates the devastating consequences of racism and gives us several key issues to think about. Sallie asks a good question when she says, “And if they were bold enough to kill a rat or find a rat already killed and put it in my locker, who’s to say they weren’t bold enough to not be joking about hurting my boyfriend?” (284). Because life is messy and good literature reflects life, readers will find good, bad, and ugly elements in this book–food for thought.

- Posted by Donna