Twelve years ago, Frances Frida Ripley (aka Frankie) was born near the sea during a storm, which seems to have imprinted on her, making her prone to volatility and moodiness. She is often impatient with her six-year-old sister, Birdie, and temperamental with her parents. Given her outbursts, Frankie has grown accustomed to her father’s admonishment: “Shouting creates negative energy and harmful interpersonal toxicity. Plus, it messes with our heads” (19).

Twelve years ago, Frances Frida Ripley (aka Frankie) was born near the sea during a storm, which seems to have imprinted on her, making her prone to volatility and moodiness. She is often impatient with her six-year-old sister, Birdie, and temperamental with her parents. Given her outbursts, Frankie has grown accustomed to her father’s admonishment: “Shouting creates negative energy and harmful interpersonal toxicity. Plus, it messes with our heads” (19).

Frankie is frustrated by how adults always try to sort out or tidy up feelings, putting labels on them or nudging them into another shape. When Frankie doesn’t get her way, she rages. Her parents are forever trying to get her to refocus her anger on an alternative thought, to “break the thought pattern that isn’t serving [her] and try to think in a new way” (95).

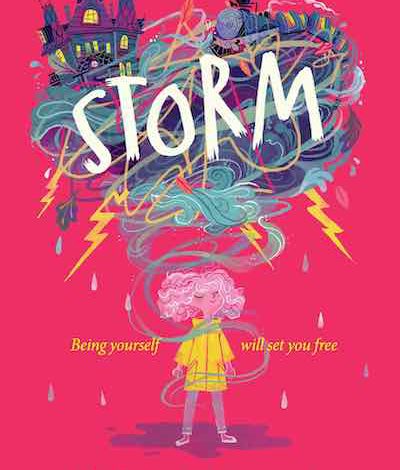

Through her protagonist, Frankie, in the novel Storm, Nicola Skinner explores the complexity of human emotion. Using clever analogies, Skinner shares various theories with her readers who are left to decide for themselves where strong emotions go if we’re not allowed to feel them.

After a freak earthquake on the coast of France sends a shock wave to the community of Cliffstones, the resulting tsunami wipes out the entire village. Now, Frankie is dead, a ghost separated from her family who strayed from home that day because of one of Frankie’s tantrums. When Jill, a death chaperone on the bus for twelve and unders, comes to collect Frankie, Frankie—ever the trouble-maker—refuses to join the Afterlife Club and board the bus.

Jill explains that “as a stubborn, hard-headed, challenging type” (75), Frankie didn’t die properly. With unfinished business or something still on her “to do” list, Frankie is left behind with a vial from Jill with directions to drink the vial’s contents when she gets home. The vial, a sleeping potion for the dead, promises to dissolve the worst of Frankie’s loneliness and to awaken her when anyone walks through the door.

One hundred and two years later, Frankie awakens to the voices of two men who have discovered a time capsule from the tsunami of a century ago. Soon, a crew is cleaning, restoring, and rebuilding. The result is a museum of sorts with holograms. “Thanks to our digital archive restorers, we were able to download the Ripley family home videos from their computers, mobiles, and tablets. And we’ve copied and cloned their voices with the help of found footage. So, this twenty-first century family can welcome twenty-second century guests to their home” (127).

Realizing that the joys of solitude and privacy are lost in the future, Frankie now feels “abandoned in a stitched-up monster house” (130) that has become a tourist attraction. From those who come to visit this home from the past, Frankie also discerns that “true happiness is the biggest secret in the world. . . . as impossible to capture as mist” (195). With the relics the family left behind, all the tourists see is what Frankie’s family didn’t have. Yet, Frankie begins to realize all she did possess. Angered by their pity, Frankie becomes a poltergeist, destroying elements of the museum.

Then, she meets Scanlon Lane, a loyal, kind, clever but motherless boy who can see ghosts. Scanlon invites Frankie to “brain gage IRL” (184), and eventually, a friendship of sorts forms. When Scanlon’s father Crawler—acting like a ghost-buster—sucks Frankie into a tuna can, Frankie wonders if the whole friendship was a con. Crawler has a collection of ghosts that he has gathered, and now that he has a poltergeist, as well, he is ready to turn his collection into a money-making enterprise called the Ghost Train.

Crawler isn’t interested in what Frankie can’t do but in what she can. Not setting limits and recognizing the storm inside her, Crawler gives Frankie permission to unleash her anger. Being seen through can, Frankie finds being allowed to get angry refreshing. All day long, she acts out her anger for the visitors of the Haunted House who drink the Ghoul Aid and ride the Ghost Train. Soon, Frankie is in love with her new identity of smashing and breaking things, living the life of a full-time, all-consuming poltergeist.

Crawler decides to rent out the star of his show for parties, and Frankie finds that satisfying until one party guest turns her back on Frankie—essentially making her invisible. “It was like dying all over again. Sometimes not being seen is the most violent thing in the world” (303). Once she experiences this feeling, Frankie gathers all of her noticings about how Crawler has slighted his other ghosts and how he treats his son. Once Frankie is determined to help the voiceless, Jill returns and helps Frankie realize that anger has power when it has a purpose.

Besides the extended metaphor of the storm, another analogy with power in Skinner’s novel is the comparison between a baby and a story. Calling each of us a “tale to be treasured,” Skinner makes clear that we aren’t just one story but “all the stories, all the time” (1). Whether an adventure, a love story, a thriller, and occasionally a horror, our lives are always page-turners.

- Posted by Donna