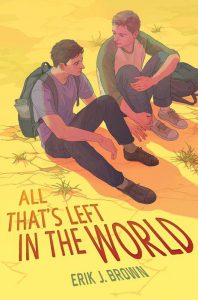

With his novel All That’s Left in the World, Erik J. Brown tells a post-apocalyptic story. It features “a gay guy, a broken straight boy, a cartography genius with PTSD, a seventy-year-old woman with a shotgun fighting zoo animals” (264), and a host of not-so-supportive others with an occasional kind character thrown in. There’s also a white supremacists commune, lest we forget the corrupting forces of racism, greed, and power.

With his novel All That’s Left in the World, Erik J. Brown tells a post-apocalyptic story. It features “a gay guy, a broken straight boy, a cartography genius with PTSD, a seventy-year-old woman with a shotgun fighting zoo animals” (264), and a host of not-so-supportive others with an occasional kind character thrown in. There’s also a white supremacists commune, lest we forget the corrupting forces of racism, greed, and power.

After a super-flu virus has nearly wiped out the American population, Andrew sets out from Connecticut on foot to find other survivors. Near Philadelphia, he is caught in a bear trap and staggers into a wooded clearing to discover Jamison’s cabin. Meant to be a reminder that kindness exists in the world, Jamison has the resources to restore Andrew’s health. However, both boys are hiding from some deeper pain.

Once Andrew’s leg heals, the two set off, hoping to discover truth in the graffiti messages that help will be arriving at Reagan International Airport. Andrew is also trying to get to the Fosters in Virginia by June 10, although he hesitates to reveal his intentions. As much as Jamison is logical yet optimistic and hopeful, Andrew leans more towards the cynical and often uses humor to deflect his pain. Andrew describes himself as “like a toxic contaminant trying to corrupt [Jamison’s] good nature” (85). Eventually, the reader discovers the backstories of both characters.

Along the way, Jamison discovers he is attracted to Andrew, and Andrew realizes that Jamison makes the world feel not so awful. Yet neither boy is eager to disclose his true feelings. And each new conflict they face together has a way of changing—even breaking—them. Andrew realizes, “We weren’t made for a world like this. Before the bug, there were rules and regulations and laws. We had years of moral code ingrained in our minds, and now none of it matters” (263). They also experience how fear makes us all do incomprehensible things.

As is often the case with good literature, Brown’s fiction reflects life and reminds us of the solace found in human goodness. After all, there is no such thing as a “good deed jar” that we fill up to earn our place in retirement or in a hereafter. All we have is the now and hope.

- Posted by Donna