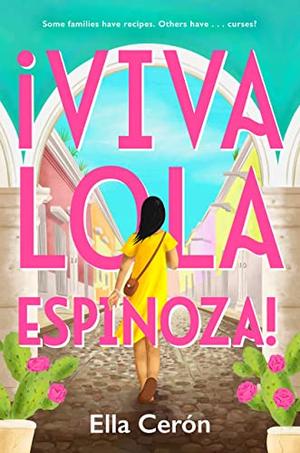

For seventeen-year-old Lola Espinoza, the main character in Ella Cerón’s first novel ¡Viva Lola Espinoza!, life is predictable and planned: sacrifice a social life and focus on earning good grades in order to get into a good college. Those expectations leave Lola feeling like she’s in “an academic purgatory with no salvation in sight. . . . There is no time for mall hangs or homecoming dances or parties or, God forbid, a relationship” (6). Although the quiet, deliberate, and introverted Lola likes being smart, she also feels like there has to be more to life than what her parents want for her; she dares to wonder about what she wants. In the meantime, she is content to live her social life by proxy, sharing in the drama of her best friend Ana Morris.

When Lola earns a C in her Spanish class, her dad decides to send his daughter to Mexico for the summer with the expectation that she return able to speak Spanish. While Lola is living in Mexico City with her grandmother, Lola’s old life in the U.S. feels distant and foreign. Besides the language barrier, the rules are different here. Buela, who can effectively deliver a searing monologue, shows her love with food but lives in fear of losing those she loves. Although most families pass down recipes, the Gómez women seem to pass on a certain doom: If a Gómez woman wishes to form her own path in life and in love, she must pay the price of misery. After Lola’s body for the second time rejects romantic attention with nausea and fainting, Lola approaches this superstition with a scholar’s rationality. The logic she has depended on all her life shifts to a looming question: What if the Gómez women are cursed?

Javier de Ávila e Idar, a server at Lola’s cousin’s restaurant where Lola works for the summer, is surly and somewhat judgmental. Still, Lola is intrigued by him and his interest in history. Javi tells Lola: “People find what they need from whatever they believe” (183). He goes on to explain that remembering history is a way to give meaning to life.

With Javi as her tour guide, Lola is determined to discover what she can about the authenticity of charms and curses and cures. In the process, she learns that the idea of authenticity is a nebulous one that undermines the truth by attempting to define something that is not so prescriptive and limiting. She also learns that she needs to live her life beyond parental expectations. “If it’s not what you want, you’ll be chasing what they want forever,” Javi offers.

Another key lesson in Cerón’s novel occurs during a makeup application video with broader implications as it discusses the concept of mistakes: “I don’t like to think of them as mistakes. . . . Everything’s a chance to practice. It’s not a mistake if you learn to do it better next time. And if you’re still bad at it next time, that means you’re human” (352).

Ultimately, Lola’s story teaches us all that we are the only people who can answer our questions because we are the only ones who have walked our path of experiences. A bookstore owner reveals this truth to Lola: “To some people, believing is the first step to making things real. Curses, blessings, they come from the same energy. Some people want magic in their lives the way they need love. . . . There are rituals that help bring comfort and some that help with clarity. . . . I like rituals because I have to participate in my own cleansing. If I want to start fresh, I have to do the work, too. The saints can’t do everything” (359). With this knowledge about spirits AND agency, Lola realizes that she doesn’t live in an either/or world and that good intentions get bigger than people mean them to be.

While reading this story about heritage and identity, my only wish was that I knew more Spanish so that I could translate certain moments in the text. Overall, Cerón gives readers a lot to think about.

- Posted by Donna